ENTREWIKI is an encyclopedia of knowledge relating to entrepreneurship – the personal as well as the corporate. Some of the posts focus on artistic entrepreneurship, while others are methods and models that can be used in teaching.

ENTREWIKI brings together theories, methods, models, approaches and directions from both practice and theory. It is all sorted alphabetically and is continuously updated. If there’s a post you’re missing in ENTREWIKI, send us an email and we’ll make sure it’s included.

The articles was originally written by Kristina Holgersen and Pernille Skov as part of the ENTRE programme.

A

Activity plan

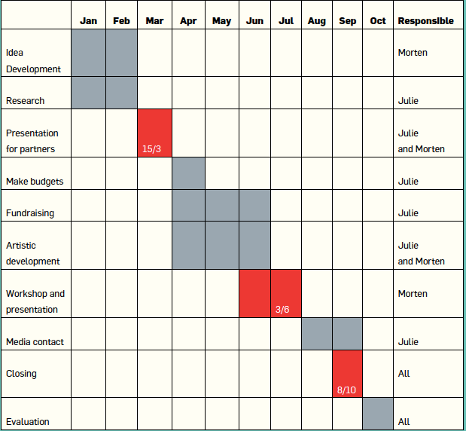

Activity plans are important management tools in both projects and companies.

Download template for a schedule here.

Agreements

As a teacher in one of the arts schools, you will often encounter students who need guidance regarding entering into contracts and agreements. In the CAKI Mini Guide – Contracts, Agreements and Negotiation you will find information and tips on what to be aware of when entering into a written contract. The mini guide also contains an array of templates to use for contracts and written agreements.

Read more here

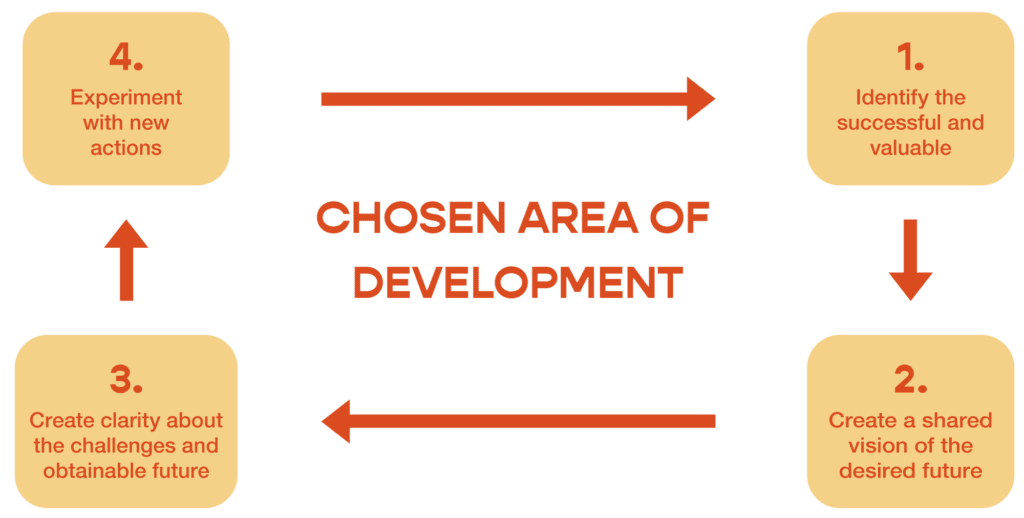

Appreciative Inquiry

Appreciative Inquiry is about the process of exploring and discovering what one as an artist or art student would like to have more of. Appreciative Inquiry is based on the idea that change and growth happen best by focusing on and exploring that which already works well. In other words, in order to discern what it is that works and to develop this.

Appreciative Inquiry further involves exploring and gaining knowledge about that which the student wishes to have more of. Appreciative Inquiry is originally developed by the American professor D. Cooperrider (Cooperrider et al., 2001). The approach is based on two main pillars. The first is appreciative, in the sense of valuing: confirming the valuable and reinforcing that which gives life and meaning. The second is inquiry, understood as exploration, asking questions, building learning and being open to seeing possibilities.

Theorist P. Lang writes, “Behind every problem is a frustrated dream – and the dream came first!” (P. Lang according to Schnoor, 2009, p. 65). Lang encourages us to focus on the dream and follow it on the basic idea that human beings thereby develop more positively and in the direction of a promising vision of the future. This is called the heliotropic principle (Greek: helios = light, trope = growth) (Cooperrider et al., 2001) (M. Schnoor, 2009).

Appreciative Inquiry’s approach is inquisitive, and the construction of the questions is completely central to determining the answers we receive. Another theorist, Barnett Pearce, is in line with Lang, but sees it from a slightly different angle: “AI (Appreciative Inquiry) contains at its foundation the art in practice of being able to formulate questions which support a system’s ability to understand, anticipate and promote positive potential (…) The questions asked of a human system will lay the groundwork for the direction in which the system will develop.” (Barrett & Fly, 2005, p. 36; in B. Pearce, 2007. More from Pearce, see also the CMM Model in ENTREWIKI).

Appreciative Inquiry opposes the more traditional examination methods in which examination and intervention are two separate processes. Every examination or learning process is an influence (simultaneity principle). Questions create thoughts, ideas and language which affect for example the student and their perception of reality. Specific questions focus our attention in certain directions, which is why it becomes important in an appreciative perspective that one as leader or teacher carefully consider what one is examining, and how it can function in the concrete context

(Haselbo & Lyngaard, 2007 according to Schnoor, 2009).

4D Model

[Chosen Area of Development]

- Identify the successful and valuable

- Create a shared vision of the desired future

- Create clarity about the challenges and obtainable future

- Experiment with new actions

Sources

Narrative Organizational Development – Forming Shared Meaning and Action, Michala Schnoor, Dansk Psykologisk forlag, 2009, p. 57-70

Communication and Creation of Social Worlds, W. Barnett Price, Dansk Psykologisk forlag, 2007

Audience

The audience, target groups and communities are essential relationships in the sustainable artistic enterprise.

For many, it can be a challenge to convey the artistic work to a particular target group,

Also, the task of creating a connection with an audience or building a community – a community – around the artistic project can be a big task. The same applies to working with your booking and generally finding places where you can perform the artistic work.

But the audience is an integral part of the ecosystem of artistic practice and business, and working with the relationship with the audience and target groups is often both enriching and inspiring.

In many industries in the cultural sector, reports and studies have been made that deal with the audience in particular. You can find links to them at the bottom of this post.

You can also read the CAKI Handbooks Startup, Idea Development and Project Management, PR & Communication and Fundraising for more information on how you can relate to an audience in the artistic business.

Connecting Audiences Danmark (May 2022)

Kulturbarometer 2022-2023 (2022)

Rapport: Førstegangsgæsten til koncert (November 9. 2022)

Artist Statement

An Artist Statement is a relatively short text that you write as an introduction to your practice and work.

The text is aimed at both industry and the public, and it serves as an aid to others’ encounter with you and your work. It can be used on websites, in applications, as an introduction to the CV, in publications, in connection with PR work and other places where a practice or an artistry can be presented in writing in a short format.

Artist VAT

Artist VAT can be applied to certain original art works, productions and services. Some art students need to register their business with a CVR number. Therefore, you may encounter students who need knowledge about the tax rules that apply to their particular type of artistic business. The rules for tax registration and payroll tax are part of the knowledge one needs when registering a business.

Read more about sales tax, artist tax and payroll tax in CAKI’s Miniguide here.

Artistic narrative

“(…) A story is not just a story. It is in itself a localized action, an expressive performance. It works in the direction of creating, maintaining or changing the world of social relations.” Social Construction – Entering the Dialogue, 2004, Gergen/GergenThe artistic narrative has an impact on the possibilities the artist has for creating relationships in or mentions about the artistic practice. Regardless of whether or not the artist uses the story, it still affects the way we perceive the work of art or artistic product and/or the artist. As such, it is always relevant for the artist to develop the knowledge of how a narrative practice can unfold.

In the narrative practice, storytelling is experienced as a creative activity. In other words, one creates reality in the language one uses, and these realities are kept alive and circulated through narratives. According to psychologist Harlene Andersen, language has a creative power:

“‘Language is not innocent!’ Every time we tell a story, we bring forward a special reality while pushing many other possible realities to the background.” – from Narrative Organizational Development, 2009, Michala Schnoor.

For many artists, their personal story and life experiences have a clear impression on the artistic process or the artistic product. For others, the personal story is more of a background for their practice.

The 7P Model can be applied as a tool for testing narratives or to open a conversation about personal stories. The 7P Model can create a perspective on how an artist can work actively with storytelling and thereby how we can communicate with the world around us.

Identity as Social Construct

In the perspective of the narrative, identity is understood more as a relation than as something individual. The word identity implies a social process more than an individual nature: When we identify something, we give it an identity. This is a departure from the traditional cultural perspective that we as humans each have a unique, stable and cohesive “personality” that determines how we think and act. It is more an action from which something is being created. It is an expression of a person’s position or point of view more than an expression of a truth in itself.

“A person’s success in maintaining a given self-assessment depends on others’ willingness to play out certain pasts in relation to him/her. All of us are ‘woven into’ others’ historical constructions, just as they are in ours.” Gergen/Gergen, 2004

This means that the artist is actively working with creating relationships and worlds through storytelling. If one follows the narrative view on identity, it offers a position for the artist in which the artist can adopt a more relational role.

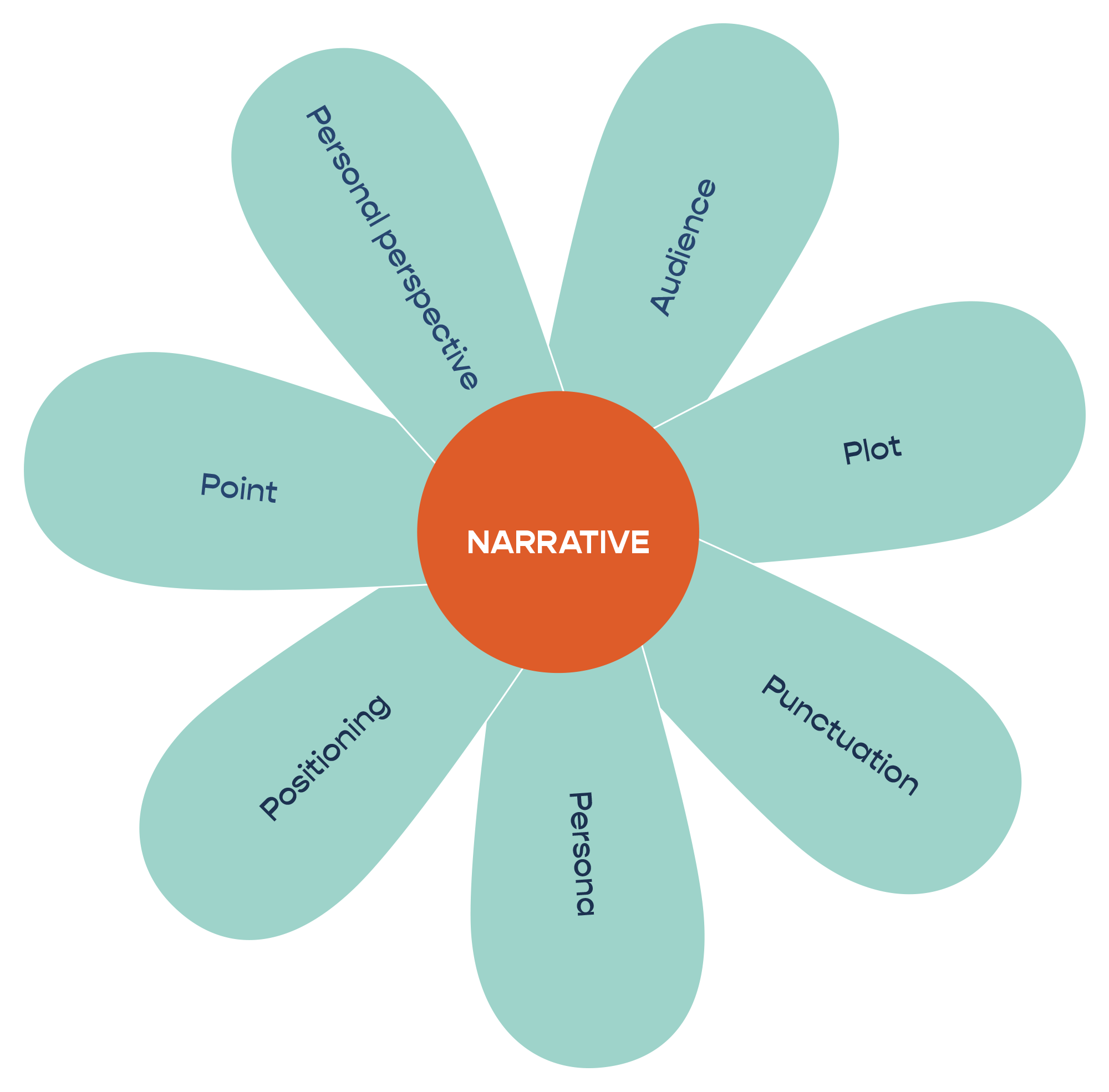

Characteristics of a story: The 7 Ps

The 7P Model offers us a language for storytelling. The model can create a perspective on how we can actively work with storytelling, and thereby how we can communicate with the world around us.

According to M. Schnoor, narrative has a series of characteristics that make up the 7 Ps

1. Personal perspective: A narrative always has a narrator — it is always someone’s story. Psychologist Jerome Bruner calls this a story’s perspectivism. (Bruner, 1999)

2. Public: A narrative always has one or several listeners. This is where the narrative’s relational dimension resides. The narrative is shaped by the relation between narrator and public or audience — someone who listens.

3. Plot: A narrative is made up of a series of single events and actions which are linked together in a particular order in adherence with a plot. A narrative’s plot reveals what the story is about and can also be called “the red thread.”

4. Punctuation: Narratives allow us to organise our experiences in chronological order. All narratives have a beginning (past), middle (present) and an end (future). It is not always clear which event makes up each of these components of the narrative. We create meaning in our experiences by selecting certain events over others, so something is pulled to the foreground instead of something else. Part of this selection process is what communication theorist Barnett Pearce calls punctuation — determining where the narrative begins and ends.

5. Personae: A narrative always contains a group of characters who act in relation to each other. These are the personae. Some actors play leading roles while others play supporting ones. Once a character or action is determined by the story’s narrator, it will likely maintain its identity or function throughout the story. An interesting characteristic of narratives is, however, that they create connections between the exceptional and the ordinary (Bruner, 1999). In other words, narratives contribute to creating meaning in actions and behaviors that deviate from the predictable.

6. Positioning: A story, because of its plot and the discourse from which the story springs, makes available certain positions. These positions help form both identity and room for possible actions.

7. Point: A story always has a moral or point. The point in a story is the lesson the story wants to bring forward to the audience. The question is, how does one form a story so that others will be likely to want to listen and take an interest in the moral message?

Fig. 7P model:

Sources:

- Text based on Narrative Organizational Development, 2009, Michala Schnoor

- Meaning in Action, 1999, Jerome Bruner

- Social Construction – Entering the Dialogue, 2004, Gergen/Gergen

Artistic Business

“Artistic Business” is the title of one of the themes in the ENTRE PROGRAM, a program we offer to teachers at art schools. One of the focuses of “Artistic Business” is how to build an artistically and economically sustainable business. Read more about the program here.

Artistic Citizenship

Artistic Citizenship is in focus on several of the higher artistic educations and appears etc. in the strategy for the Royal Academy of Music and the Rhythmic Conservatory of Music has in 2020 established a research centre for artistic citizenship. In ENTRE, which is the art school’s joint program, for the development of entrepreneurship as a field of knowledge, artistic citizenship is also a theme. In this article, you can read more about what is meant by artistic citizenship and where the concept comes from.

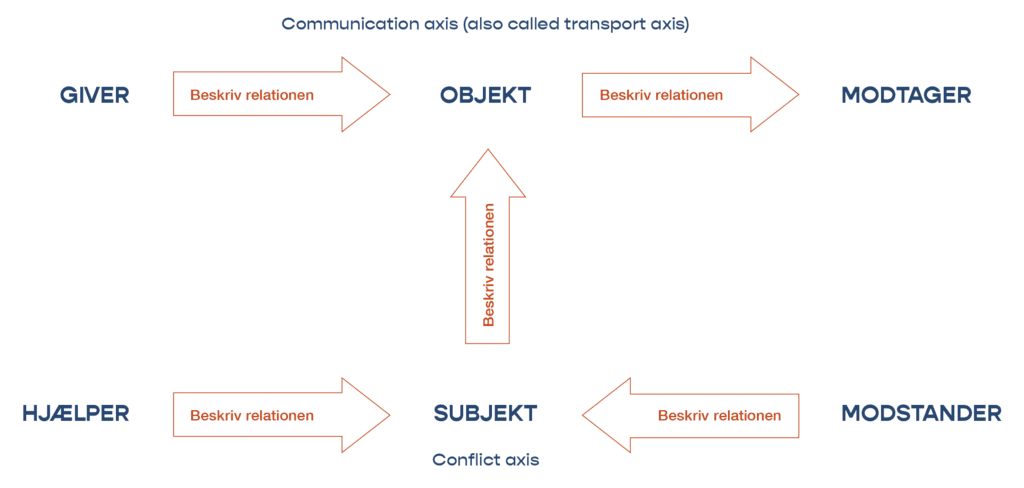

The Actant Model

The actant model is an analysis model. It provides an overview of the most important people and their relationship to each other in a story.

The word ‘actant’ comes from Latin, where ‘actus’ means action. An actant is one who acts. The actant model is a model where we get an overview of who is acting in the story. In the model, there are six actants in total. The actant model was originally developed to analyze folk tales. We can also use it when we need to analyze other kinds of stories, such as films. The actant model is generally best used for the analysis of films with external conflicts.

The actant model is based on the narrative’s main character (the subject) and the person’s project, i.e. battle or mission to achieve its goal (the object). The protagonist’s project is the most important thing in the story, and what the story is about.

However, the model can also be an effective tool for initiating development processes through narrative scenarios. The special strength of the actantial model is that it serves as a checklist of the key players of the project while creating a coherent picture of relationships, functions and possible actions. In short, the actantial model can be used as a tool for identifying possible development strategies, planning projects and communication.

The participant model consists of 6 roles, which are denoted actants:

- Subject – Who is the “main character”?

- Object – The subject always has a project, a goal or something that he or she wants.

- Opponent – Who or what tries to prevent the subject from getting the object?

- Helper – Who or what helps the subject to get the object?

- Sender – Who or what gives the object away?

- Receiver – Who or what gets the item in the end?

The actants are placed onto three axes:

- Project axis – Displays the subject (main character) and the object (goal of the main character).

- Conflict axis – The conflict axis shows the helper and the opponent who are respectively trying to help and to prevent the subject from succeeding.

- Communication axis – The end of the story is shown with the sender handing over the object to the receiver (who is often the same as the subject).

By placing the different stakeholders or concepts of your project into the 6 actant categories the logic of the development process can be clarified in a simple model, which can work as a guide for further development.

Sources:

J. Greimas (1973). Actants, Actors, and Figures. In: On Meaning: Selected Writings in Semiotic Theory. Trans. Paul J. Perron and Frank H, Collins. Theory and History of Literature, 38. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1987. 106-120.

Most of the text comes from the Innovation site, where you can also download templates and exercises using the model.

B

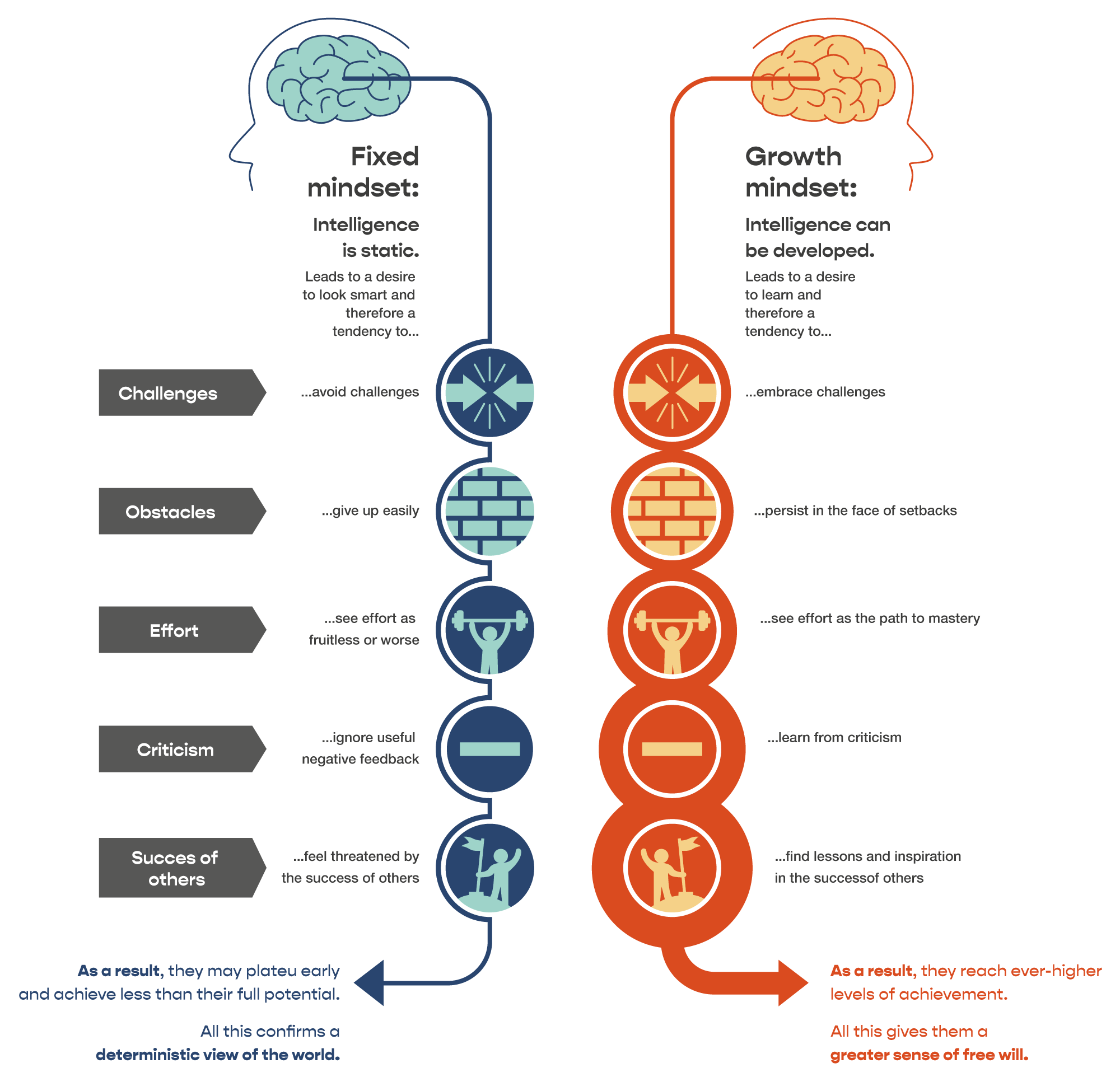

The Berkeley Method of Entrepreneurship

The method is based on the hypothesis that the mindset of an entrepreneur can be characterized by a set of behavioural patterns and that an inductive game-based teaching approach is a successful vehicle for introducing and re-enforcing these. The game-based teaching approach lets the students explore their current mindsets and compare them with those of successful entrepreneurs.

Read more here

Big Data

Since the amount of digital data from systems and social media is growing explosively, it may be appropriate to find methods and tools for processing large amounts of data. The term “big data” primarily refers to large amounts of data created by humans and systems. The distinguishing characteristic of big data is a lack of structure where data comes from many different sources, making it very diverse. Therefore, much analysis is required to process the collected data. There are many different theories, methods, techniques and tools available in the area of big data. Read more here.

Brainstorming (Idea development)

Brainstorming is one of the most well-known methods of idea development. The method is especially useful in the creating phase because it promotes the creative flow of thought.

How to brainstorm:

1. Start with a focus question.

2. Set a time limit for the brainstorm. It can be one long period or several short sessions.

3. Even though brainstorming is unstructured, set clear guidelines for the process before you start. These can include:

- All criticism is forbidden

- All ideas are welcome

- The more ideas, the better

- Combining multiple ideas is encouraged

- Ideas do not necessarily have to be realistic

4. Write ideas down on little pieces of paper

5. When the brainstorm is over, organize the pieces of paper into categories. Some may be about an idea’s form, others about content, target audience or activities.

Organizing the notes by type can help shed new light on each category. This is a good starting point for further work, for example evaluating and improving the idea.

For more information:

https://caki.dk/project/ideudvikling-projektledelse/?lang=en

https://innovationenglish.sites.ku.dk/metode/mindmap/

Sources: Idea development & Project management, 2021, CAKI

Brainwriting (Idea development)

Brainwriting is another method that is suited to the creative process. The method is an anonymous version of brainstorming and addresses several ideas at a time.

How to brain write:

1. The group is asked a focus question

2. Each person writes their answer anonymously

3. The ideas are collected in a pile

4. Each person takes an idea from the pile and has the following options;

- Using the idea to generate another idea, which is written down and sent along.

- Continuing to write about and develop or change the idea before sending it along.

5. The ideas are collected and sent along, and step 4 is repeated until you run out of time or ideas.

6. Everything is collected and evaluated.

For more information:

https://caki.dk/project/ideudvikling-projektledelse/?lang=en

https://innovationenglish.sites.ku.dk/metode/brainwriting/

Sources: Idea development & Project management, 2021, CAKI

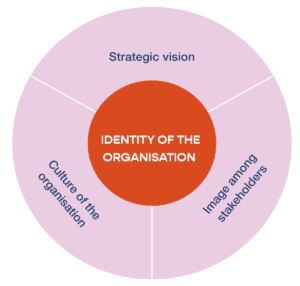

Branding and the VCI Model

It can be significant for a young artist or teacher of entrepreneurship at an art school to work with the development of the artistic brand, since it is linked to concepts in the artistic process such as identity and vision. In this article, we have chosen to use principles from Mary Jo Hatch and Majken Schultz’s book Use Your Brand. The book covers a series of four models of branding mainly intended for large businesses and organizations, but it is our experience that these models can easily be applied to artistic and even solo businesses.

The book also contains a history of the concept of branding. Branding essentially began as a type of marketing designed to create and address the relationship between product and consumer. The second wave of branding is known as corporate branding, in which many activities become centralized in and around the business. The third wave of branding centers on network thinking and focuses to a large extent on stakeholders’ relationship to business (the artistic business, for example).

Branding is used as strategic positioning, which includes discovering or creating the properties which separate a brand from the competition. Brands should also be able to attract customers and appeal to stakeholders. It reminds them of why they are or should be part of the stakeholder community around the brand.

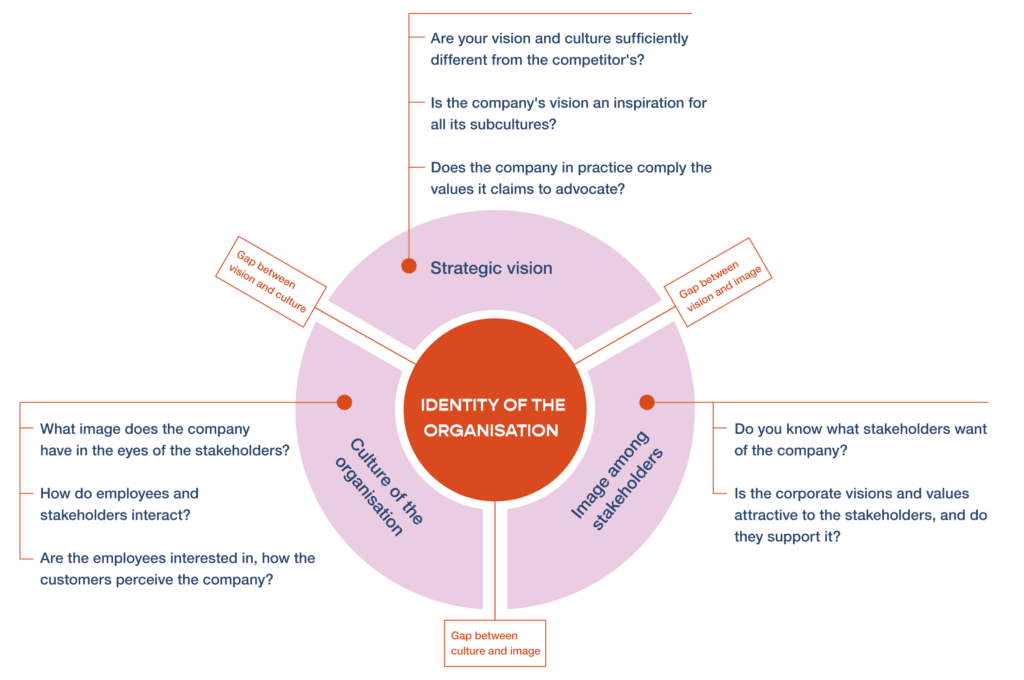

The VCI Model:

A main principle of Use Your Brand is that branding cannot succeed or function optimally unless there is a link between the strategic vision, the internal organizational culture, and stakeholders’ image of the artistic business. This is called a corporate brand, which is what we will call the whole artistic business. In every successful corporate brand, there is a noticeable link between the leadership’s vision of what they hope to achieve in the future (the strategic vision), the knowledge and beliefs of the employees (embedded in the company’s culture), and the things the external stakeholders expect of or associate with the business (their various images of the business). The founding principle is thus the link between Vision, Culture, and Image (the VCI Model). The more the vision, culture and image are united, the stronger the brand will be (figure 1.1). Conversely, a lack of consistency or too large of a gap between vision, culture and image signal a less than optimal corporate brand.

One can imagine the strategic vision, organizational culture, and the stakeholders’ expectations as pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. When spread out on a table, there is no apparent link between the pieces. Once they are put in their correct places, however, they create an integrated, expressive and satisfying whole. This creates a strong company reputation while at the same time aligning the company’s actions with the brand’s promises to all the stakeholders that make up the company. To find out if your corporate brand suffers from a lack of consistency, you may ask yourself the questions illustrated in figure 1.2..

Figure 1: Organizational identity

Strategic vision

Organizational culture

Image among stakeholders

Figure 2: Strategic vision:

- Are your vision and culture sufficiently different from those of the competitors?

- Is the company’s vision an inspiration to all of its subcultures?

- Does the company put into practice the values it preaches?

- Gaps between vision and culture

- Gaps between vision and image

- Gaps between culture and image

Organizational culture:

- What is the company’s image among stakeholders?

- How are the employees and stakeholders integrated?

- Are the employees interested in how customers perceive the company?

- Image among stakeholders

- Do you know what the stakeholders expect of the company?

- Are the company’s visions and values attractive to stakeholders, and do they support them?

Figures based on Use Your Brand, pp. 32-33.

Source: Mary Jo Hatch and Majken Schultz, Use Your Brand, Gyldendal Business, 2009

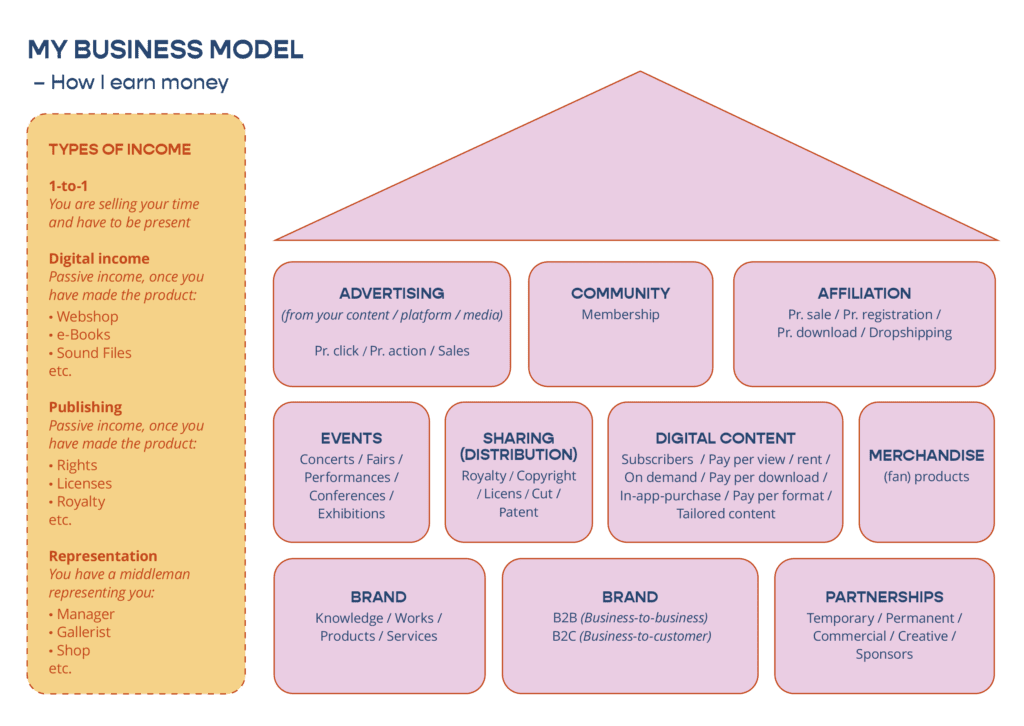

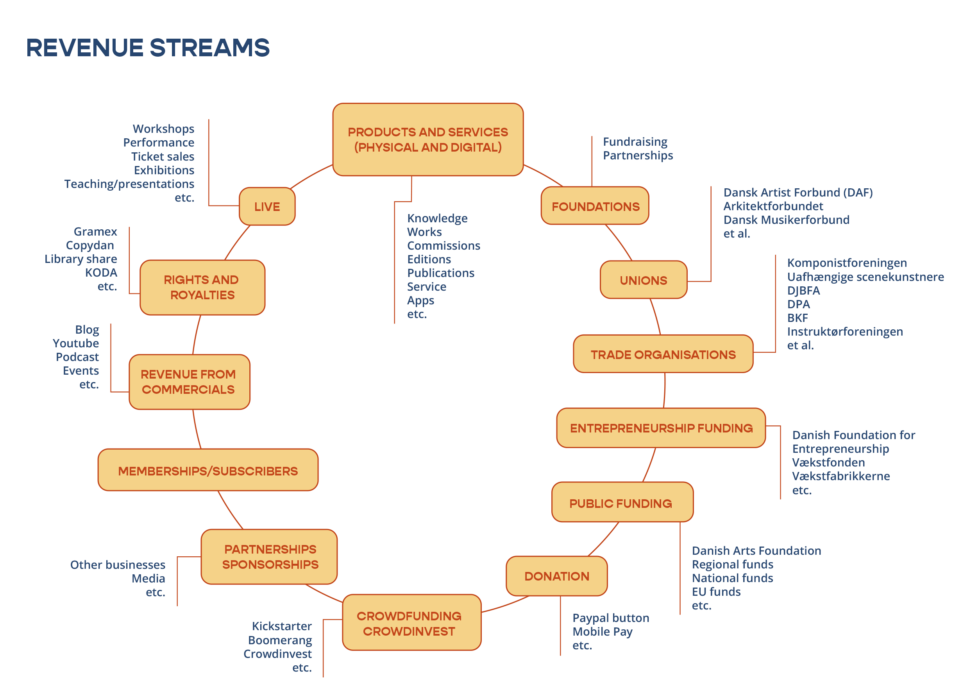

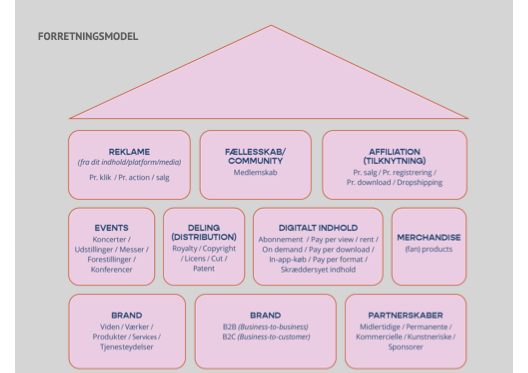

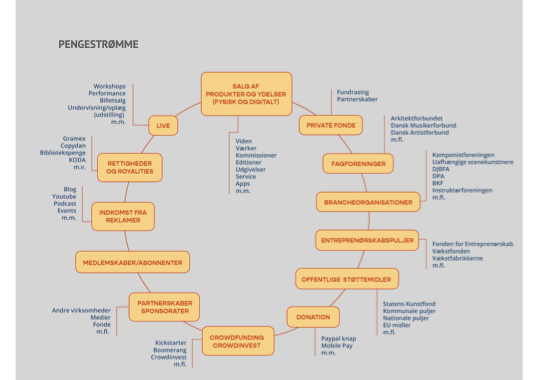

Business model

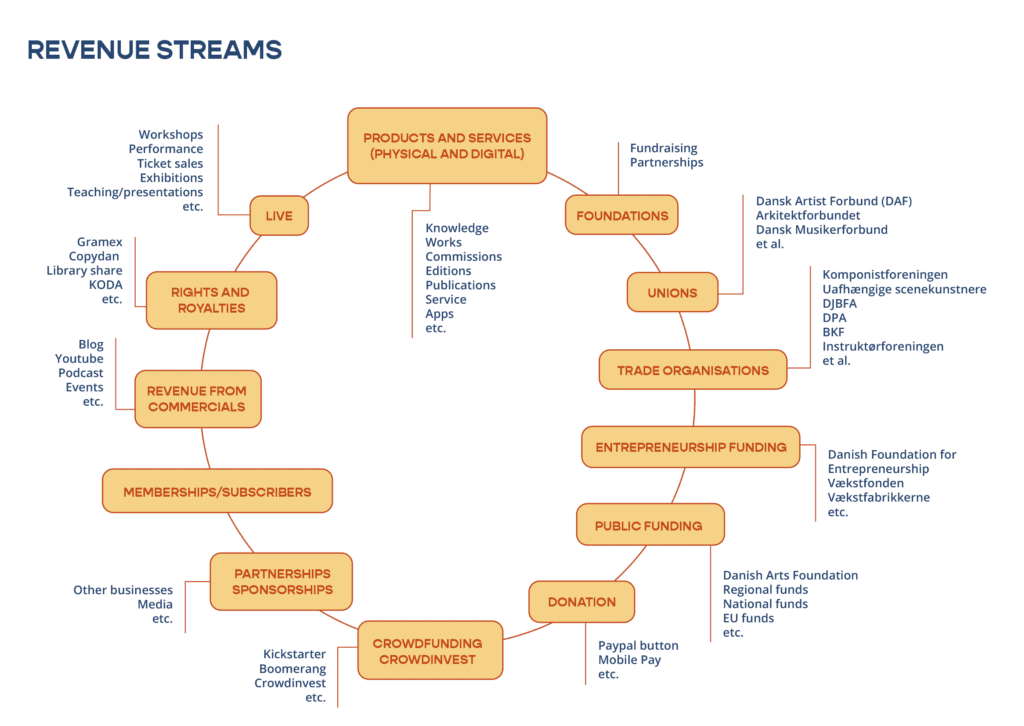

When you build a business, you should make sure that you have a variety of sources of income that generate revenue in the business. You can do this by developing your portfolio.

In a business with an artistic or cultural purpose at the outset, the portfolio will most likely contain activities that create income as well as activities that break even or even require investment to be realized.

Your portfolio is based on your professional expertise and your interests as well as the need to create an income that can support you. Creating a sustainable practice and business for yourself requires that your business creates enough revenue to pay your business expenses while also providing you with an income since you must be able to afford food, rent and other basic expenses.

Not every activity will make an income for you, but realizing a basic income to support yourself should be a goal of your business. This means you should determine which parts of your portfolio are profitable.

Most people with a business in the cultural sector can have a broad and versatile portfolio – from producing original artworks and/or productions to consulting and teaching, which are some of the most common examples. The variety of tasks will depend on your specific artistic field as well as your professional profile. In the beginning, you may have to perform some tasks or say yes to jobs that are not part of your dream scenario. This is normal, since building a sustainable profession takes time.

Think about which products and services in your practice can generate an income and then combine them into a revenue-generating portfolio. Since you may have activities in your portfolio, which do not lead to income and perhaps even is an expense, you should arrange your work so the profitable activities pay for the non-profitable activities.

You decide how your portfolio should look. During the establishing phase of your professional life as self-employed, it can be wise to focus on the activities which make money and work toward building a sustainable business around them. That way, you can stabilize your economy, which will give you freedom in the long run.

Do a thought experiment where you imagine all the possibilities of where your practice can lead. Think about all the products, works and services you can create or provide. Be creative!

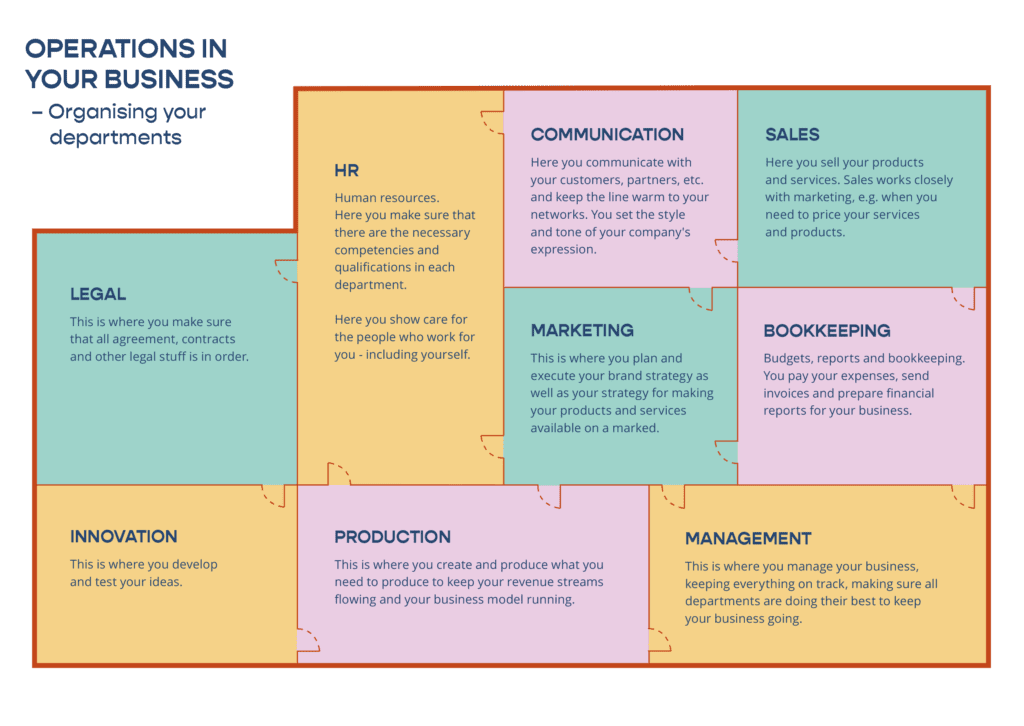

Model: BUSINESS MODEL

The model has been developed by Maiken Ingvordsen and Pernille Skov as part of The Art of Start Up (2018)

Business Model Canvas

Business Model Canvas is a model that can provide an overview of the artistic business as a whole. It can be used in individual artistic practices as well as large cultural businesses. The model is a communicative and analytical tool which allows us to discover and explore the elements of a business, for example, the artistic and commercial partnerships and how these interact with the other building blocks of the business. The model works well in teaching entrepreneurship, but it is also a useful tool in the artistic development business, for example when working with students to explore and develop the many ways the artistic practice might play out in a given situation.

The model is developed by theorist Alexander Osterwalder. Osterwalder looks at a company’s business model as a description of how an organization or business creates, delivers and captures value. He illustrates this approach in what he calls the business model canvas.

The approach is presented in the publication Business Model Generation. Here Osterwald describes how a company’s activities can be divided into a series of building blocks which make up the company’s basic activities. The building blocks are: partners, activities, resources, offer of value, customer relationship, distribution channels, expenses and cash flow.

Business Model Canvas is in its design split into a left side which is internally oriented around expenses (cost) and a right side which is customer oriented around value. For example, if a business wants to reach customers through new channels (a building block on the right side), partners (a building block on the left side) will presumably change. Perhaps you decide to have your business shift from using live channels (exhibitions, concerts, cinema screenings, etc.) to online distribution. The change in distributional or promotional format presumably means you will need to find new partnerships that can help your business move forward.

In short, Business Model Canvas is a model that helps us explore and develop our business model in a systematic way.

Read more about the approach in the book Business Model Generation. A free download of 72 pages of the book is available at this link. You can download the template for Business Model Canvas here.

Business Model Generation

In 2010, Alexander Osterwalder published the book Business Model Generation, which focuses on the way we work with business models. The education system in particular has embraced Business Model Generation.

The book Business Model Generation describes how a company’s activities can be divided into a series of building blocks. The approach is a strategic and analytical tool which allows us to discover and explore the elements of a business, for example the artistic and commercial partnerships and how these interact with the other building blocks of the business.

The elements of the business are defined by:

Partners, activities, resources, offer of value, customer relationship, distribution channels, expenses and cash flow. Business Model Canvas is the model for this approach. The model is in its design split into a left side which is internally oriented around expenses (cost) and a right side which is customer oriented around value. For example, if a business wants to reach customers through new channels (a building block on the right side), partners (a building block on the left side) will presumably change. Perhaps you decide to have your business shift from using live channels (exhibitions, concerts, cinema screenings, etc.) to online distribution. The change in distributional or promotional format presumably means you will need to find new partnerships that can help your business move forward. In short, Business Model Canvas is a model that helps us explore and develop our business model in a systematic way.Read more about the approach in the book Business Model Generation. A free download of 72 pages of the book is available at this link. You can download the template for Business Model Canvas here.

Business registration

It is free to register a personally owned business. We cover the process step by step in CAKI’s Miniguide to Registration of a Personally Owned Business. Read more here.

Business Start

Some art students need to register their business with a CVR number. You may therefore encounter students who need information about starting their own business.

CAKI’s Handbook: Startup is written for the full spectrum of artistic fields and business types — from soloists and production companies to one-person businesses and Ltd’s. The handbook covers all the general questions you need to consider when starting a business of any size.

Get the handbook here.

Business Types

There are many different business types, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The most important thing is selecting the type that fills your needs in terms of what you do in your business.

Read more in CAKI’s Miniguide to Business Types here.

C

Changeboards

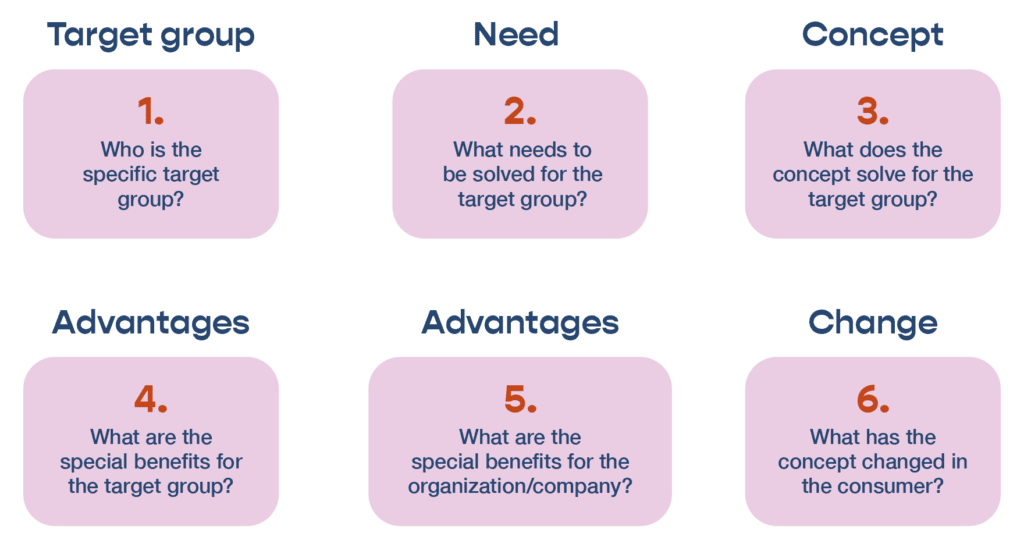

Changeboards is a visualisation tool that can be used to support and structure the development, evaluation and communication of user-oriented concepts. The tool can be used for concept development after the initial idea development.

Changeboards visualises six user scenarios that, when combined, create the change scenario of the concept. In order to create Changeboards please answer the following questions:

- Target group: Who is the target group (users) and what characterises them?

- Need: What does the target group need to be solved? Why is it important for this group to have it solved? What is the purpose of the concept?

- Solution: How does the concept solve the problem of the target group? What is the concept’s core experience? Why is the concept’s core experience relevant for the target group?

- Benefits for the target group: What are the particular benefits for the target group (users)? Why is the target group interested in your particular concept? Does the target group have a reason to return to your concept?

- Benefits for customers: What are the particular benefits for the client/customer? Why is your concept better than other similar concepts?

For the students to satisfactorily answer the above questions they need to work visually with storytelling scenarios because the visualisations can reveal the atmosphere, challenges and beliefs much more clearly than words. Please use the template in the column to the right on this page.

- Scenario – visualise the target group as a typical user.

- Scenario – visualise the user’s need.

- Scenario – visualise a solution that suits the need.

- Scenario – visualise the user’s use of the solution.

- Scenario – visualise how the user benefits from the solution.

- Scenario – visualise the significant changes and consequences that the solution has on the user’s daily life.

Developed by Katalyst, Faculty of Humanities, University of Copenhagen. Based on the NABC principals, Stanford Research Institute.

Sourced from https://innovationenglish.sites.ku.dk/metode/changeboards/

Chaordic organization

The mix of chaos and order is often described as a harmonious coexistence displaying characteristics of both, with neither chaotic nor ordered behaviour dominating. The chaordic principles have also been used as guidelines for creating human organizations – business, nonprofit, government and hybrids—that would be neither centralized nor anarchical networks.

Characteristics of Chaordic Organizations:

- Based on clarity of shared purpose and principles

- Self-organizing and self-governing in whole and in part

- Exist primarily to enable their constituent parts

- Powered from the periphery, unified from the core

- Durable in purpose and principle, malleable in form and function

- Equitably distribute power, rights, responsibility and rewards

- Harmoniously combine cooperation and competition

- Learn, adapt and innovate in ever-expanding cycles

- Compatible with the human spirit and the biosphere

- Liberate and amplify ingenuity, initiative and judgment

- Compatible with and foster diversity, complexity and change

- Constructively utilize and harmonize conflict and paradox

- Restrain and appropriately embed command and control methods.

The text is sourced from the CIO Wiki: https://cio-wiki.org/wiki/Chaordic_Organization#cite_ref-1

Read more about the characteristics of chaordic organizations here

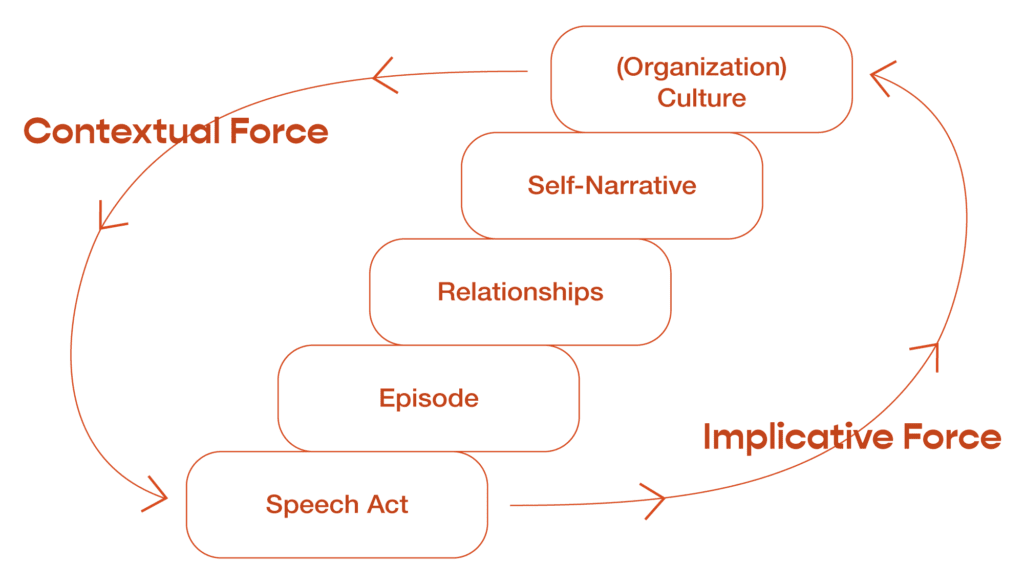

CMM Model

The CMM (Coordinated Management of Meaning) Model is developed by two American professors of communication, Barnett Pearce and Vernon Cronen.

The CMM Model addresses how we as artists can make a difference through our choice of communication. Further, the model focuses on the idea that, through our speech acts, we can participate in changing the world.

The model can be used to clarify for example which culture an artist is speaking to or belongs to and how contextual force influences that. Conversely, the model also reveals how our speech acts, episodes, relationships and self-narratives have implicative force (consequences) and thereby influence a culture.

A focus on the contextual force allows for reflection and meaning making by constantly directing our attention outward toward the influences the students experience through cultural discourse, which affect their self-stories, relationships, episodes and speech acts. This makes it possible to have a reflexive relationship to media, literature and other materials expressed by authorities with knowledge and power in art and culture.

A basic principle of the CMM Model is that there are always many contexts at play in a conversation. Many misunderstandings arise because we usually take it for granted that the person we are talking to is operating in the same contexts as we are.

Pearce and Cronen say themselves that, with their model, they are introducing a communications perspective on our actions. It is a perspective which enables us to look at communication rather than through it.

The model relates itself to so-called dialogic communication. Pearce and Cronen draw upon appreciative inquiry to delve into the speech acts which constitute (as basic units) our sentence constructions and their combinations.

Speech acts create episodes and relationships which affect our narratives (self-stories) and the culture around us. We thereby become aware of our linguistic acts right down to the construction of types of questions and their expected resulting answers along with where we can act differently in communication. (Moltke and Molly, editors, 2009, pp. 245-247)

References

Barnett Pearce: Communication and the Making of Social Worlds, Danish Psychological Publishing, 2007

Hanne V. Moltke and Asbørn Molly, editors: Systematic Coaching: A Primer. Danish Psychological Publishing, 2009

Talk: Barnett Pearce on Coordinated Management of Meaning:

Communicating in writing - 10 tips

10 tips for clear, concrete and energetic writing

1.Write to your receiver

Your language depends on your receiver. If your communication is aimed at a partner or colleague who’s already familiar with your project and its terminology, you can use a more internal and theoretical language than if you are communicating with others who are not familiar with your project or your subject. Only use theoretical and technical terms if you are certain your receiver understands them.

ASK YOURSELF:

What prerequisites does my receiver have for understanding me? Is the receiver already familiar with me or my project?

2. Make your writing easy to read

Avoid long sentences, convoluted formulations and passive voice. Use periods; divide the text into short paragraphs, and only make one point per sentence.

Avoid writing something like this:

“With a mixed crowd of regular users, guests in open workshops and attendees in international artist-in-residence workshops, the old brickworks will once again come abuzz with life, entrepreneurship and creativity.”

Instead, write:

”The old brickworks will once again buzz with life, an entrepreneurial spirit and creativity. This will happen as regular users, guests in open workshops and attendees in international artist-in-residence workshops occupy the brickworks.”

3. Be specific. Use details

Specific details make the project tangible and understandable to the reader. Not all details ought to be included. Choose the ones that are particularly telling of your project and which can help emphasise your message.

4. Need to know vs. nice to know

Prioritise, prioritise, prioritise! Your receiver doesn’t need to know everything about your project. If you shower people with too much information, your core message will get lost in the process. Cut to the bone.

5. Avoid filler words and blah blah blah

Delete redundant words and phrases such as ‘really’, ‘many different’, and ‘in relation to’.These words only make your point fuzzier and your text less clear.

Avoid writing something like this:

“The overall goal of the communication efforts is the involvement of many different stakeholders and target groups that will serve as a pivot to ensure the exhibition is highly successful.”

Instead, write:

“The purpose of communication is to involve stakeholders so the exhibition can be successful.”

6. Show, don’t tell

Good examples and illustrative writing helps make your project tangible and engages the recipient.

Avoid writing something like this:

“The exhibition is an atmospheric universe of various aesthetically linked works.”

Write:

“The audience steps into a darkened gallery where six white marble sculptures are lit by separate floor lamps. When the audience approaches the sculptures, the light changes colour from white to red while the room is simultaneously filled with smoke and the sound of a bass increases in volume.”

7. Appeal to reason and emotions

Make sure to give your recipient good arguments and appeal to their senses and emotions. For example, you could bolster your arguments with facts, statistics, authorities and experts, while employing illustrative language with good, recognisable examples stir emotions in your receivers.

8. Use direct speech

“Did you see that?!” “No, what?!” Direct speech can make the text come to life and stirs the reader’s curiosity. It also helps using direct speech in headings and subheadings.

9. Surprise

Employ humour, controversial claims or an unusual angle. This could include funny, surprising statistics or juxtaposing two things that one wouldn’t usually link together, such as flying pigs, beautiful monsters, etc.

10. Remember to proofread!

Typos, grammatical errors and misplaced commas leave the receiver with an impression that you are sloppy. And if you do not spend time on your writing, why should your receiver spend time reading it? Always proofread, and if you can, have a second pair of eyes read it over.

TIP:

If you are in doubt about where to place commas and periods, read the text out loud to yourself. This is often a good way to tell where to insert breaks and periods.

Get the handbook.

Sources: PR & Communication, 2020, CAKI.

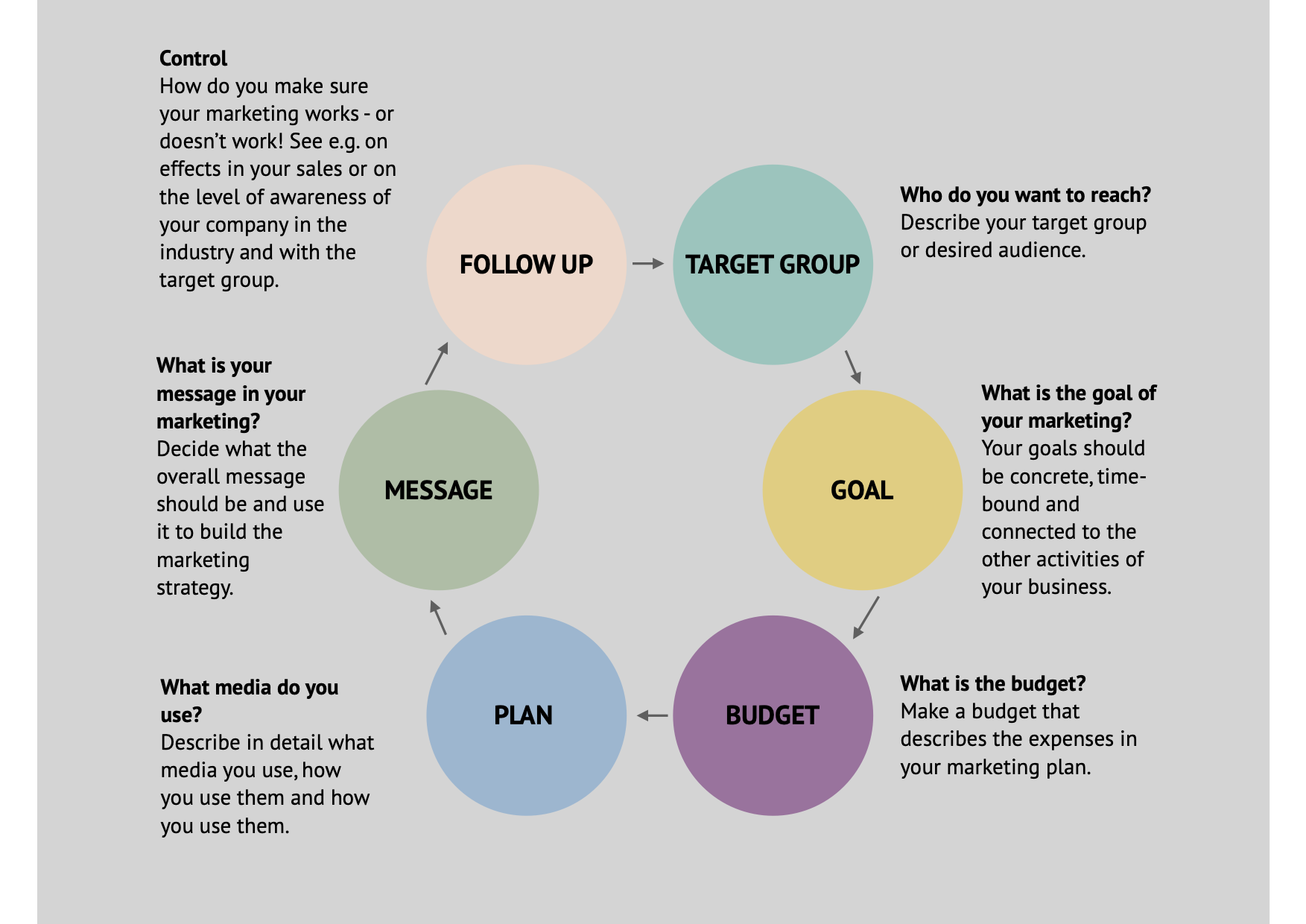

Communication

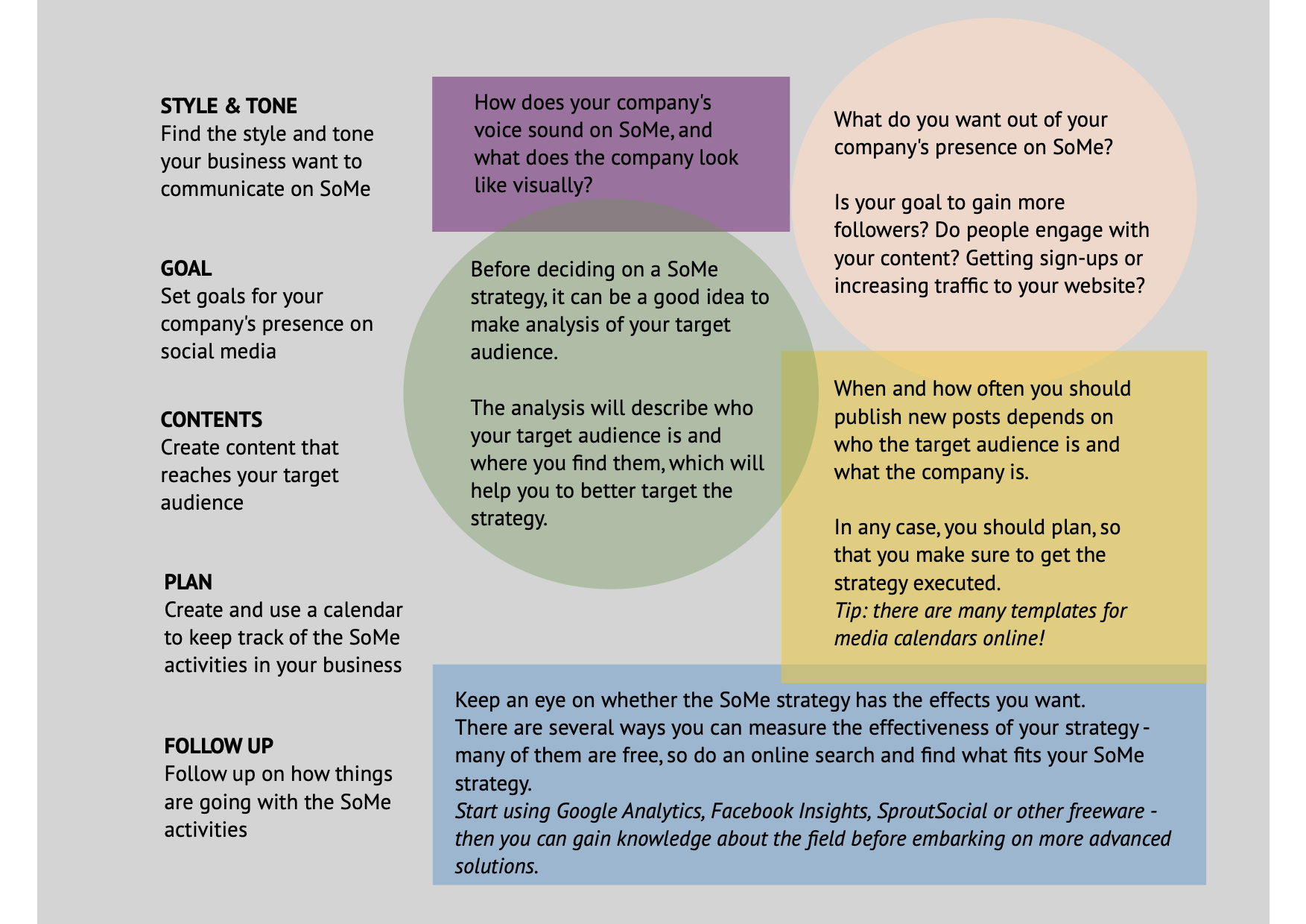

Set a goal for yourself

Generally, your communication efforts as an artist can be based on one of two factors: your artistic profile or your project.

Your artistic profile

where the focus is on you as an artist. Your communication is not limited to a specific time period but occurs continuously through your choices in relation to how you make your work visible as well as on blogs, websites, Facebook, etc.

A project

where your focus is on raising awareness of an artistic project, e.g. a concert, performance, film or exhibition. Your communication is designed as a process that unfolds over a certain period of time.

Set a goal for yourself

Communicating inherently comes with the implication that you want to achieve something through communicating. It could be that you want an audience to attend your show, get your project mentioned in the media or to get more followers on Facebook. In other words, you have a goal for your communication. Strategic communication is about moving from one position to another:

A → B

From your current position/your reputation/your project’s current level of publicity (A), to a better position/an improved reputation/more publicity of your project (B).

ASK YOURSELF

What is the purpose of my communication?

Where do I want to end up?

What do I want to achieve?

(B)

What is my starting point?

Do I already have a profile or brand I want to strengthen? What resources are at my disposal?

(A)

Keep in mind that good goals are ambitious, realistic and require commitment. In order to help you achieve the goals you have set, it can be very helpful to set a (long-term) plan that you can follow. Later in the book, we provide you with a template on how to lay out such a plan.

Your situation

Once you have formulated your goal, you need to find the path that leads to it; making the right choices and decisions that help you get there. All communication consists of five components:

- Topic

- Receiver

- Language

- Medium

- Sender

These five components are interlinked in what is called the communication situation in technical terms. You should therefore consider all those components before laying down your communication plan. Changing one component may have implications on the other components, changing the way in which people perceive your project. In the next few pages, we will review the five components and provide you with some exercises that can help you shape each component appropriately in relation to your situation.

Topic

Far too much communication ends up becoming too abstract and intangible for the recipient. This is often due to the fact that the sender has not clearly determined the core of the artistic idea or creative concept before communicating about it. The quote below comes from the introduction of a project description in an application. But what is the project about? Why is the format unique, as they start off by claiming? And what artistic perspectives, performances, discussions and workshops are they referring to?

“The project is a unique format of non-formal education. Students will bring their own unique artistic and generational perspective to various performances, discussions and workshops; the question of working with non-material art in the time of total production will be discussed from different perspectives.”

It’s fine for the introduction to arouse curiosity in the mind of the receiver, but in the above example, the questions result in confusion and uncertainty rather than sparking interest and curiosity. And that simply won’t do. Before you begin communicating your project, you should understand your project and its essence, and you should be able to put it into words. It’s often very helpful to write a thorough project description that describes the purpose of the project and defines its content, the receiver and the form of communication.

Make project description

If you haven’t already got a project description, we recommend that you make one. In CAKI Handbook ‘Project Management and Idea Development’, we guide you through the process of writing a project description.

Get the handbook here.

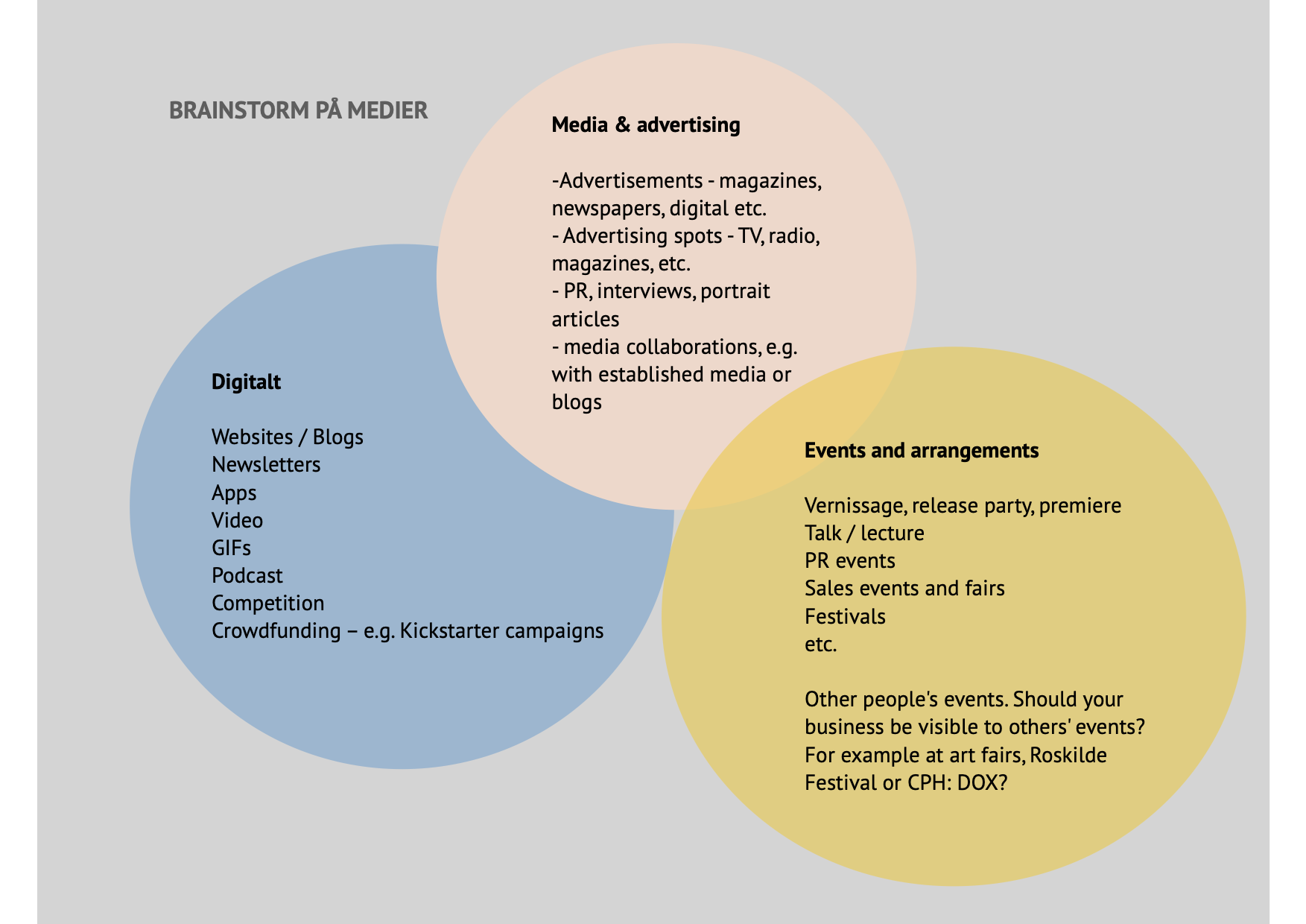

Communication & Media

Medi

Communication and PR are more than just press releases and ads. It can also include events, social media, lectures, blog posts, happenings, etc. In art and culture projects, there is ample opportunity to set up creative and alternative communication channels. For instance, you may want to mark the start of an exhibition with a happening or performance, or perhaps a short teaser film. Alternatively, you could write a blog post about the process from start to finish? Make sure to set aside time for idea development to find the right way to communicate your project.

Choice of medium

On the opposite page, you will find a list of different types of media and communication channels. This list is intended to serve as inspiration. Only use the media and channels that make sense to you, your project and your target groups.

Exercises for the evaluation phase

Media and communication channels

- Exhibition opening, release party, premiere, etc.

- Lectures

- PR events

- Rehearsal performances/concerts/etc.

- Sales events and fairs

- Festivals

- Oral pitching – e.g. to companies or strategic partners

- Events hosted by others. Should you and your project be present at other events than your own, such as art fairs, Roskilde Festival or CPH:DOX?

Media & advertising

- Advertisements – magazines, newspapers, digital, etc.

- Advertising spots – TV, radio, magazines, etc.

- PR

- Interviews and profiles

- Media collaborations, e.g. with established media outlets or blogs

Digital

- Website

- Blog

- Newsletter

- Freebees – give parts of your project away for free as an appetiser

- Social media (Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, LinkedIn, Tumblr, etc.)

- Apps

- Video

- GIFs

- Podcast

- Competitions

- Crowdfunding – e.g. Kickstarter campaigns

Adapt your communication to the medium

Always adapt your communication to the medium.

For example, if you want to make an oral pitch to a number of potential partners, you need to factor in their short-term memory, using simple language and short sentences and repeating your points.

On the other hand, if you want to use Twitter as your primary communication channel, make sure to familiarise yourself with hashtag culture and get comfortable with articulating yourself in 140 characters or less.

ASK YOURSELF

Are there any special circumstances, traditions or rules I should take into account in relation to this communication channel?

Is it up close or remote communication?

Is the channel formal or informal?

How do I best disseminate my message through this specific channel?

Get the handbook.

Sources: ´PR & Communication, 2020, CAKI

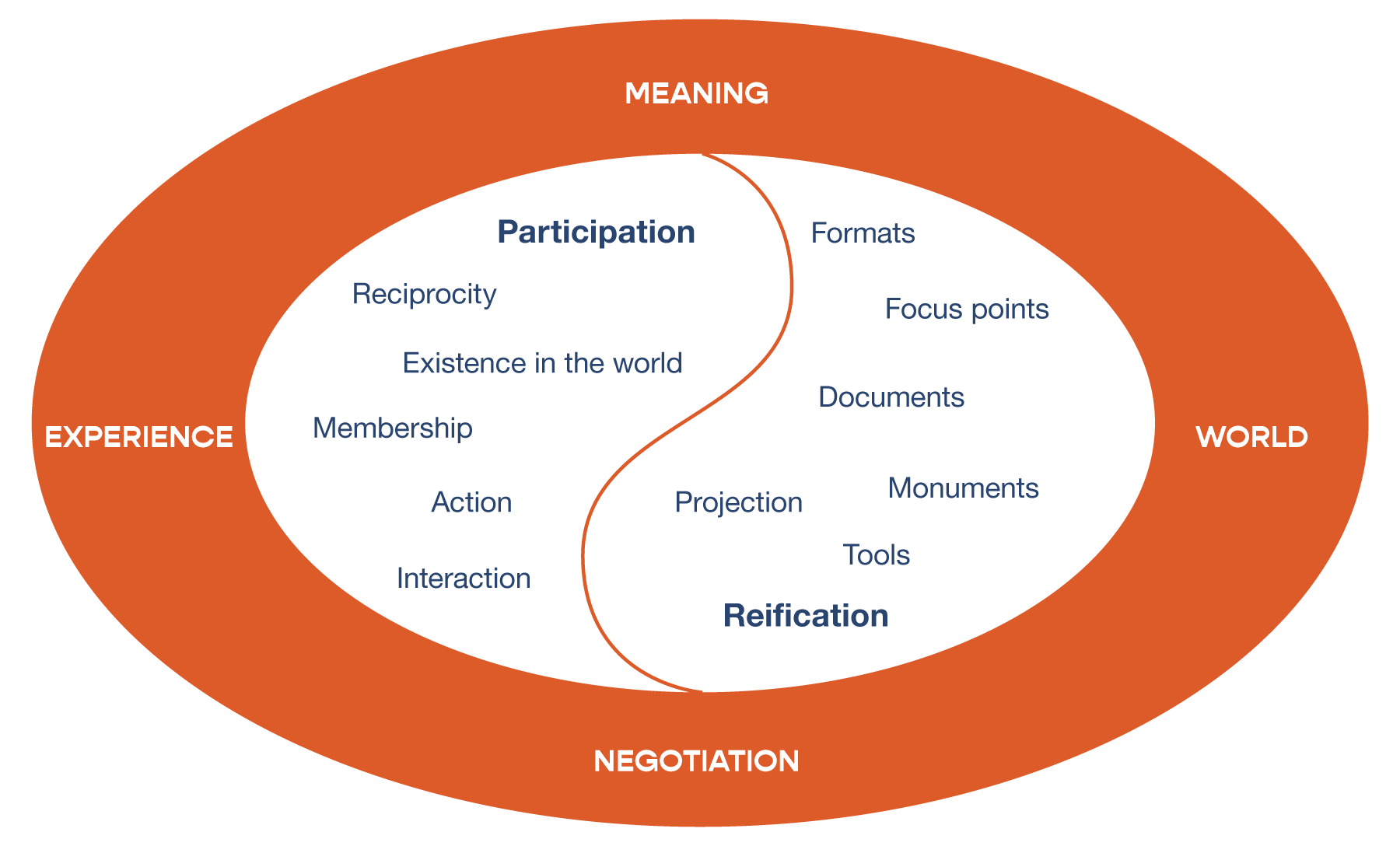

Communities of Practice

Etienne Wenger’s idea of communities of practice focuses on how we as artists can see ourselves as active participants in social communities.

There are communities of practice everywhere, according to Wenger. We all have an affiliation to communities of practice: at home, at work, in school, through our hobbies — we belong to many different communities of practice at any given time. They can be both formal and informal. As artists, we are part of a wide range of communities of practice, including fellow students in a class, work groups and production teams — all of which may be formally structured, and informal groups such as roommates, fellow diners in the cafeteria, or even the smokers on the terrace.

When Wenger uses the expression “communities of practice,” he uses it as an introduction to a broader terminology for understanding learning. Wegner does not make any distinction between theory and practice with regard to human experience and knowledge: “The relation between practice and theory is always complex and interactive. Meaning exists not as something fixed, but in the dynamic relation, and is therefore subject to change,” says Wenger.

Practice constitutes our actions in a historic and social context, and engagement in practice always involves the whole person and both the action and the knowledge simultaneously.

“We all have our own theories and ways of understanding the world, and our communities of practice are places where we develop, negotiate and share them” (Wenger, 2004, p. 62).

Wenger focuses on learning as social participation — being an active participant in social communities, practicing and constructing identities in relation to these communities.

See and hear Etienne Wenger at the ENTRENord Conference, CAKI 2014 here.

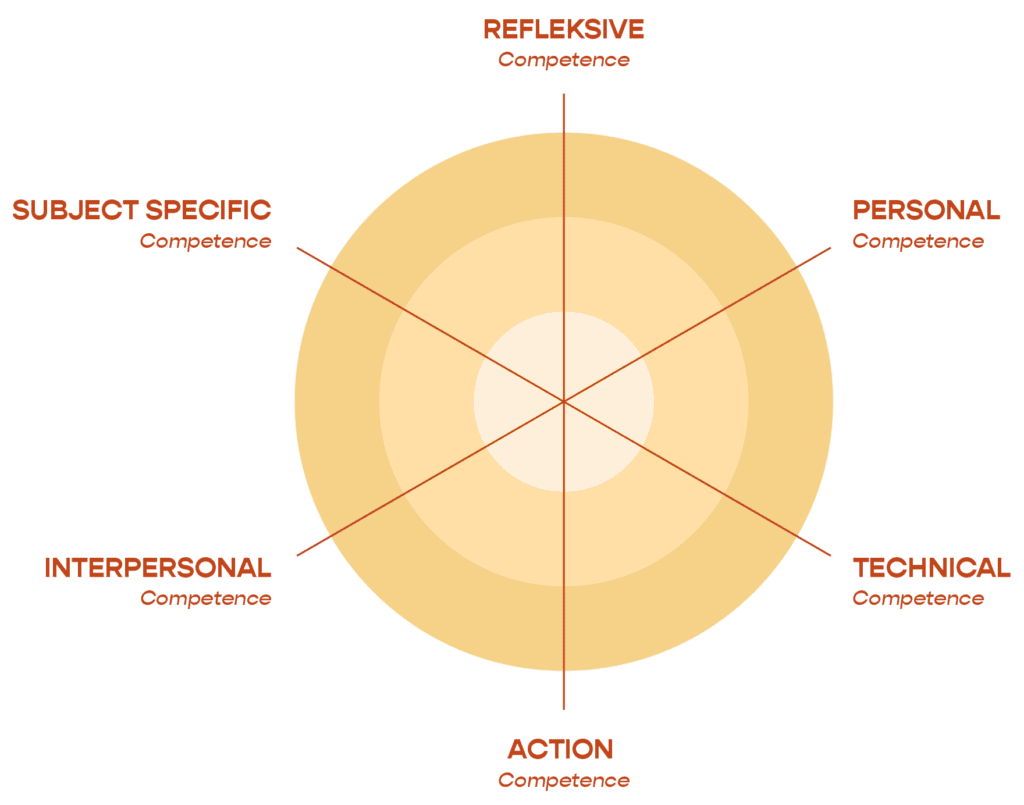

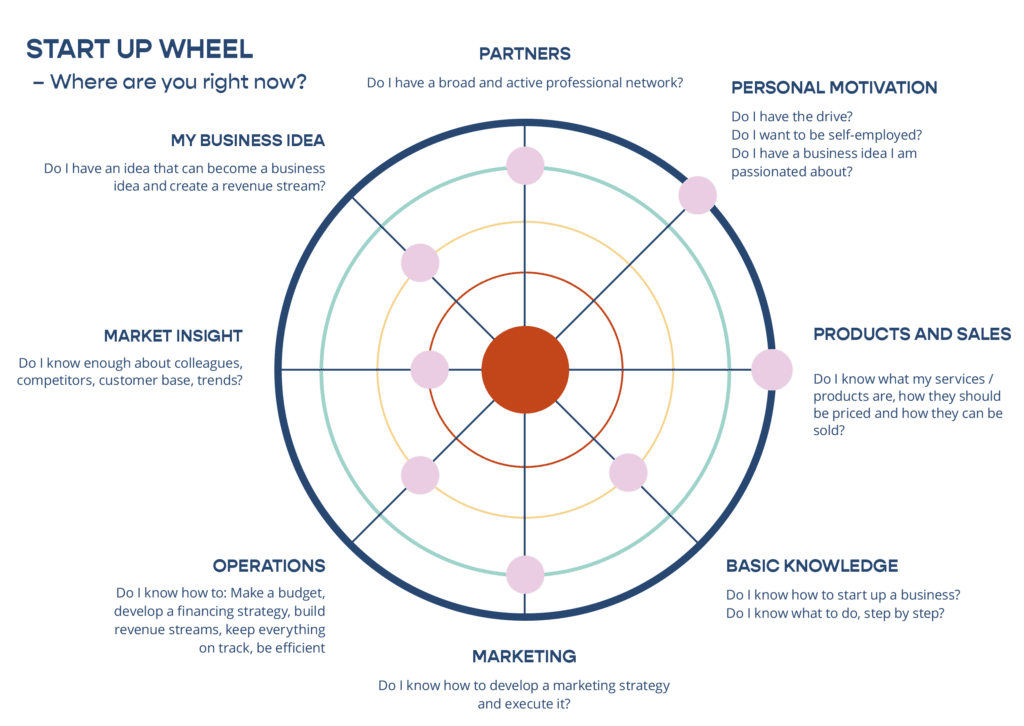

Competence Wheel

Development of a competence profile

As an artist, it is central to be aware of your competencies and to be ready to develop the skills which need to be improved in order to develop your professional life.

Competence development is an ongoing process, and it is important to give yourself time for the process to unfold. You can use the competence wheel in different contexts by putting on different caps, for example: “my competencies as an artist”, “my competencies as a teacher”, “my competencies as a leader of artistic processes”, etc.

By filling in the competence wheel, you can get an overview of where you can develop your skills. Go through the wheel and tick the lines according to how developed your skills are. Think about where and how you can expand your skills in relation to your future professional life.

The competence wheel has been developed by business economist Jan Molin. Molin believes that only you can fill your competence wheel. Personality tests and profiles created by others will not necessarily reflect the reality you yourself experience.

Fill in the model

- You place a cross on the line (e.g. the line for action competence). The closer you place the intersection to the centre, the less you assess your competencies. The further out of line, the higher the competence.

- Assess your own competencies for all six areas of competencies. Then draw a line from the cross to cross. You will get your unique spider web in the chart.

- Then make a document in which you describe why you have placed your competencies as you have in the diagram. Write 2-3 lines.

- Now select 1 or 2 competencies that you will purposefully work on improving. You cannot develop many skills at the same time. Give yourself time to reflect on what you can do to improve e.g. technical competencies if that is the one you choose. Write 2-3 lines.

For example

Technical skills: I am considering how I as artistic director of a project can create better documentation of our work. What technical solutions are available? What does it cost? Is it something I myself can become good at? If not, who should do it?

Bring the model into play with fellow students, a teacher colleague or project partners. Then you get the opportunity to put words to your movement within a given field of competence and can get feedback when you have worked with the development.

Action skills

Is about being an active agent. Are you good at realizing your projects? To initiate artistic activities, projects and coordinate work tasks, finding partners and raise investment funds?

Are you outgoing and energetic? Can you turn thoughts into action? Do you work purposefully to achieve your goals?

What can you get better at – and how?

Reflective skills

Do you give yourself time to stop and think about the direction you are moving in?

Are you good at finding inspiration and researching in your artistic practice?

Can you see your actions in perspective? Can you have a dialogue with others about what it does? Does it make you act differently?

What can you get better at – and how?

Personal skills

This is about your personal development and your focus on yourself as an artist. This is where you look inwards and reflect on who you are professionally and what competencies and skills you would like to develop – e.g. your skills as reliable, conscientious, humorous or something completely different.

What can you get better at?

Interpersonal competencies

What are you good at in relation to your collaboration with other people?

Ex: are you aware of other people’s limit, are you open, empathetic, confrontational, conflict-seeking, reliable, good at giving space or do you prefer to be alone? Etc.

What can you get better at – and how?

Subject-specific competences

In relation to your artistic practise – what is your repertoire?

Are you good at: Expressing yourself artistically, specific artistic processes, rehearsing, reaching a goal, collaborating in the artistic space, perseverance, leadership, etc. What are your experiences?

What can you get better at – and how?

Technical skills

What technical tools and qualifications do you possess and which do you need? E.g. techniques, technical equipment, production tools, use of spreadsheets for budgets, communication tools? Do you have the programs needed to develop what you want – and do you master them so that you can put your subject-specific competencies into action?

What can you get better at – and how?

Read more here.

Source: Carlshøj & Co, ‘Sådan udfylder du dit kompetencehjul’, 2019

Contracts

Many art students will probably already under their studies need to know how they enter a transaction or how to agree on a fair contract. This is because an oral agreement or a handshake is not always enough to avoid misunderstandings. In CAKI Miniguide – Contract negotiation for Artists we advise you to pay attention to a number of things when you ensure a written agreement. In the Miniguides there are a number of templates of contracts and agreements which you can freely use.

Read more here.

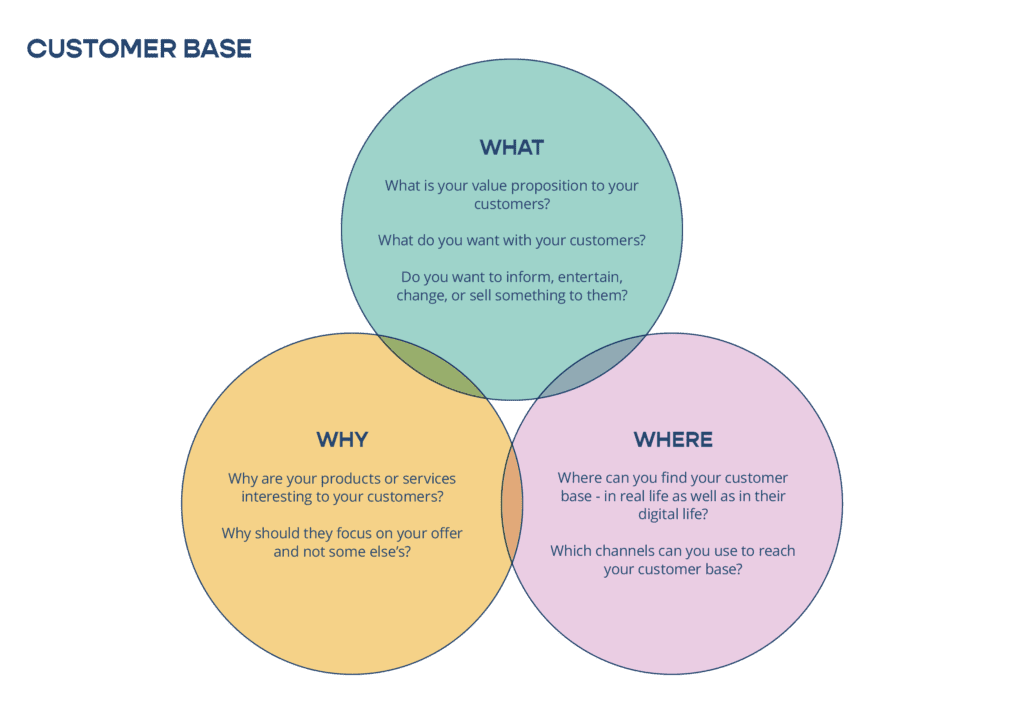

Costumer base

Thinking about who is going to pay for your products or services is key if you want to be able to support yourself from the income in your business.

Many artists and creatives do not think about their customer or target group in the creative phase of making their art or developing products or services, and that is okay. But in order for you to make money from your work, sooner or later you will have to think about and communicate with your customer base. That is the only way you can help them buy what you are selling.

The customer base and the primary target groups are those who will have a need fulfilled or get an advantage or benefit (e.g. aesthetic, sensual, experiential, practical or economically) by purchasing, using or experiencing your product or service.

A secondary target group can be individuals, organisations or companies that have an interest in having your product or service reaching a target group. They are buying what you are selling but on behalf of someone else. In some situations, they will become the primary target group. For instance, if you are fundraising, foundations can become a primary target group. Or if you are selling events for kids, the parents become an important target group.

MODEL: Custome base.

Finding your customers via your value proposition

Your value proposition is what makes people or companies turn to you and not to someone else. The value proposition is composed of a selection of products and services, and sometimes also of your profile as an artist or creative – based on the fact that there is only one you.

As such, the value proposition creates value via a mix of elements. Values might be qualitative (e.g. design, status or risk reduction) or quantitative (e.g. price or speed).

Here are some examples of what values could be (not an exhaustive list):

Newness – customisation – design – brand/status – performance-price – accessibility – cost reduction – risk reduction – usability – convenience

CV

A CV is an overview of a person’s professional experience. When you apply for funding, grants, scholarships, education or a job, you always include a CV in your application. While the application usually describes your motivation or project, your CV quickly and precisely shows your educational background and professional experience. The same goes for the CV you post on your website or as part of your online portfolio or LinkedIN profile – here your CV also needs to quickly and clearly state your educational background and your professional experience.

Fundamental considerations:

- Start your CV with your name and contact information. You can also include a portrait photograph, but it is not required. If you use a picture, consider the photograph’s appearance. If you choose a conventional portrait shot, always be sure the photo is sharp and in focus. If you choose a less traditional portrait format, you can choose a more experimental visual style.

- Your CV should always include the category headings Education and Professional Experience. Consider which section the recipient will read first, and present them thereafter in chronological order. It is most common to put the education section first, since it is usually the shortest category.

- In addition to your professional work, you can also include other relevant experience, such as having served on the board of directors of an association, volunteer work, etc.

- Categories: If for example you have exhibited your work, performed concerts or have had works published, dedicate a special category to this. This can also be courses, tours abroad or other relevant qualifications you want the recipient to be aware of.

- If you have a very extensive CV, it may be a good idea to curate the content if you are targeting a specific employer or collaborator. It should certainly include everything you are proud of, but you can still be strategic and tailor your CV, for instance by highlighting assignments in the areas you want to work in in the future.

- Always list items in a category in chronological order beginning with the most recently started activity. If the activity is finished or you already know when it will be finished, write the start year and the expected end year. If the project is not finished, keep the end year open, but still put the start year first.

- Describe your experiences, but keep it short! If you only write a job title, it can be difficult for the recipient reading your CV to know exactly what you did in a specific position or assignment. It will therefore be useful to include a short description (a minimum of one line) of exactly what you did and what your assignments consisted of. You may choose to write it in keywords to keep it short.

- Use several different CVs. When using the CV in a job application, try as much as possible not to exceed one page. In an application process, you want to give the recipient a quick overview of your experience by showing the best of what you have done. In contrast, when using a CV on your website or LinkedIn profile, you can include more experience and use the CV to keep track of what you have done. When using your CV for artistic collaborations, you might want to put the primary focuse on your merits and experiences with your art form.

- Consider your writing style and your layout. Your writing style and layout can say a lot about who you are, so consider what style is best for the application. If you want to be able to use your CV in several different situations, choose formal language and fonts.

- Write correctly! You must ALWAYS proofread your CV, and you should also ask another person to proofread it for you. Your CV should be completely free of spelling mistakes and grammatical errors.

- Use air in your layout. Make sure your CV is easy to read for the eyes. Use margins and line spacing to create a simple overview. Keep the sections aligned to avoid disturbing the natural readability.

Creative alternatives and platforms:

It can be a good idea to use creative formats and platforms to present your CV. For instance, you can combine your CV with a portfolio, sound files, film or a digital platform. Just keep in mind that it should be consistent with the way you want to be perceived. If you aren’t sure about how to proceed with your CV, then stop and reflect before you continue. You can also ask a peer to have a look at it to get their opinion.

D

Dialogic Communication

Barnett Pearce provides the field of artistic entrepreneurship with a useful supplement to the more instrumental “transmissions theory of communication.” The instrumental tradition is prominent in for example how-to literature with its fixed templates for communication and marketing on various platforms.

Pearce’s theory of communication can be viewed as challenging the conception of communication as the transmission of information from one individual to another, which Pearce calls the transmission model. It is most effective when the message clearly and precisely expresses the meaning intended by the sender and is interpreted in a way which closely matches that meaning. Pearce believes this often fails because language’s meaning is negotiated in relationships (B. Pearce, 2007, p.39).

Instead, Pearce presents a social constructive model, or what he calls dialogic communication. Here communication is more a way to create the social world and is always practiced together with others. Rather than “What did you mean by that?” the more relevant questions are “What are we doing together?”, “How do we do it?” and “How can we create better social worlds?” (Pearce, 2007, pp. 39-40)

Pearce and Cronen, who together developed the CMM Model (see elsewhere in ENTREWIKI), also draw upon Appreciative Inquiry. In the CMM theory (Coordinated Management of Meaning), the two authors delve into our speech acts, which constitute (as basic units) our sentence constructions and their combinations. The effects of speech acts are called language’s implicative force (ed. Moltke and Molly, 2009, p. 245).

Speech acts create episodes and relationships which affect our narratives (self-stories) and the culture around us. Conversely, context affects us (contextual force, as Pearce calls it) in such a way that the culture affects our self-stories, which in turn affect relationships, and speech acts (ed. Moltke and Molly, 2009, p. 247).

“We are inclined to see what we know, rather than the other way around, and our ability to latch onto bifurcation points and make smart decisions about how we should proceed at these bifurcation points requires sharpened conceptual tools for understanding communication.” (Pearce, 2007, p. 19)

References:

Barnett Pearce: Communication and the Making of Social Worlds, Danish Psychological Publishing, 2007

Hanne V. Moltke and Asbjørn Molly, editors: Systemic Coaching: A Primer, Danish Psychological Publishing, 2009

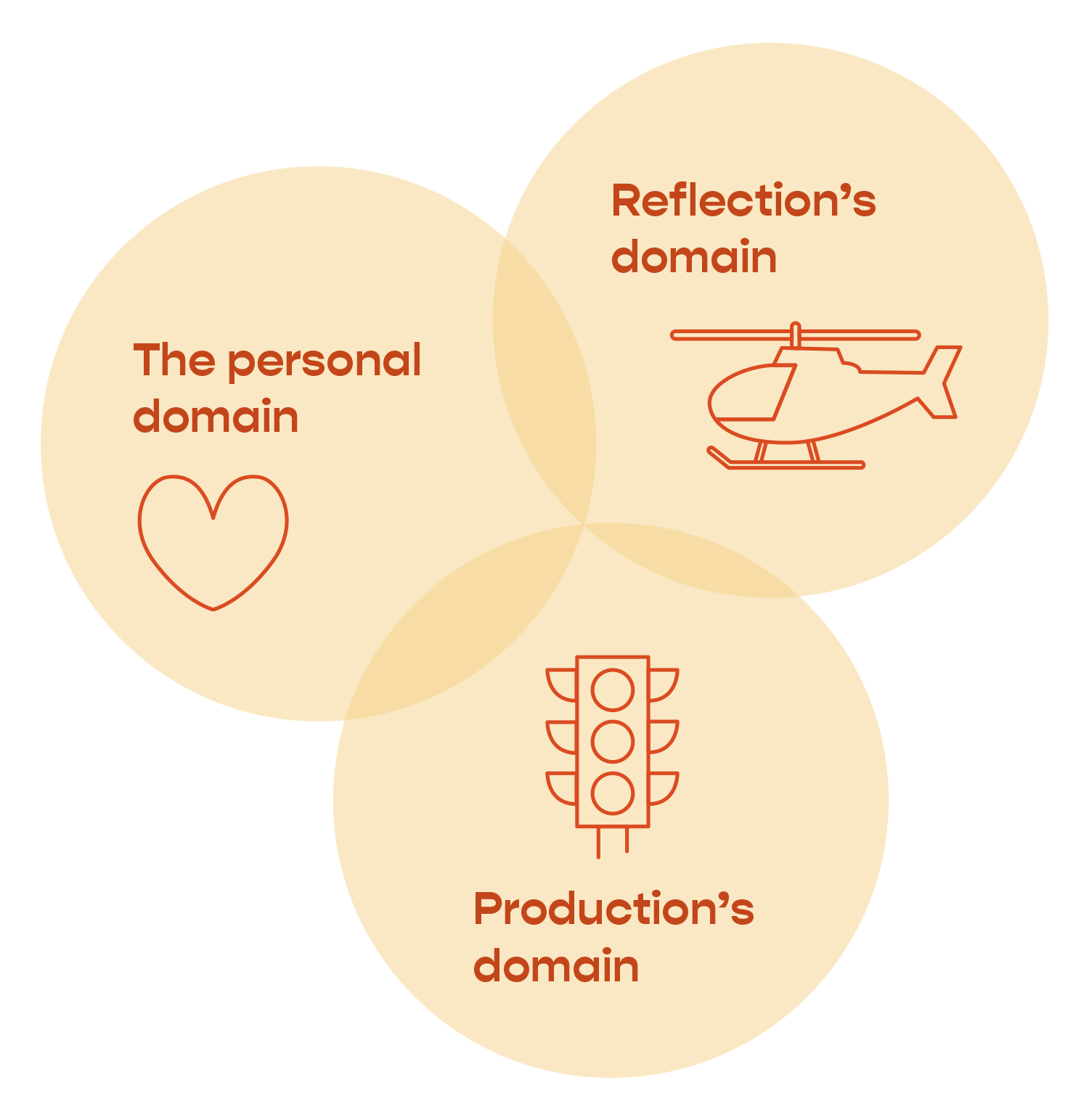

Domain theory (the communicative domains)

The domain theory is created by Peter Lang, Vernon Cronen and Martin Little based on the work of Humberto Maturana. When the domain theory is interpreted as a tool, it becomes a dialog tool that can be used to work with social relations in the artistic business. The tool clarifies the social and relational dimensions of the work and is especially applicable when treating complicated or sensitive topics in an artistic practice for example in the mental working environment. The domain tool structures the discussion of the topic and sets specific dialog rules which create confidence, transparency and openness to the different viewpoints.

Introduction to Domain Theory

Domains can be seen as communication “rooms” that one enters and exits through the conversation. Each room has its own unique language and logic which describe specific elements and angles of an issue. In other words, special codes of language and logic govern each domain (room).

The domain theory is an attempt to clarify three separate logics which we use to see, understand and describe the world. The domains (logics) exist side by side in the conversation, but as a rule, one of the domains is dominant at a given time compared to the other two. The three domains are the personal domain, the domain of production and the domain of reflection.

The Personal Domain

The personal domain is the language designated by the participants’ values, morals and ethics. Here the participants cannot relate neutrally but take personal positions based on what they consider to be good practice. In the personal domain the participants speak as private individuals with their attitudes, emotions and opinions. They have personal positions based on how they experience the situation.Regarding the topics of mental working environment and work pressure, the participants’ communication in the personal domain will for example address what each member considers a reasonable workload, how they define their personal limit of work pressure, and what creates good processes and job satisfaction for the individual.

The Domain of Production

Opposite the personal domain is the domain of production. This domain concerns the rules, routines, guidelines and already adopted procedures that are the basis for the artistic work and which govern specific situations and tasks. This domain is where the participant or co-worker speaks about the established way of doing things. Unlike in the personal domain, one cannot decide for themselves what is right or wrong in the domain of production. One follows the already adopted procedures and guidelines — just as in traffic rules where everyone knows green means go and red means stop. For this reason, in the domain of production, leaders primarily perform their leadership tasks. When one addresses work pressure in the domain of production, the conversation will usually address prioritization of job tasks, expected quality level and standards in task solutions as well as procedures and rules for job performance. Thus, large problems are created in this domain when there are conflicting interpretations of what the rules are, what is right in specific situations, and the correct course of action (compare to the example with traffic signals).

The Domain of Reflection

The third and final domain is the domain of reflection, in which the world is considered subjectively. Unlike in the personal domain, in this “room” we are more open to others’ viewpoints, and our own experience or opinion is subject to reflection. In this domain, it is less interesting to reach a final conclusion than to hear others’ perspectives on the subject and develop a new understanding together. When we address the subject of work pressure, in the personal domain we are biased by our personal experiences and values, while the domain of production restricts us through authority and the rules of the community. However, in the domain of reflection, it is possible to lift ourselves above the subject together in order to see the problems of work pressure from new perspectives.

Practical Application of Domain Theory

The objective of applying domain tools to create better mental working environments is threefold:

- To structure communication so that dialogue follows specific steps. Knowing that the dialogue is directed and structured creates stability and predictability in regard to a complicated and sometimes delicate subject.

- To consider as many perspectives and logics in the mental working environment as possible through communication about the mental working environment. Holding a dialogue about the mental working environment in each of the three domains consecutively ensures that the group will gain a thorough understanding of all perspectives on the subject.

- That communication about the mental working environment in different domains enriches each other, creating a fertile ground for new understandings and ways of acting. For example, a dialogue in the domain of reflection can help add new understandings to the individual participants’ subjective understanding of his/her mental working environment in the personal domain and inspire new agreements about how to proceed in the domain of production.

As a bonus, using the domain tools has the added effect of strengthening the participants’ ability to identify which domains govern different situations and to recognize when disagreements occur because participants are communicating based on different domains and logics. A similarity between the domains is that they seem obvious and logical to the individual speaking. Disagreements therefore occur most often when parties communicate based on different domains (when one party is talking about their emotions while the other refers to rules and procedures, they are probably talking past each other).

Sources:

- https://www.lederweb.dk/artikler/domaeneteorien-i-teori-og-praksis/

- Systemic Coaching: A Primer. Hanne V. Moltke and Asbjørn Molly (editors), Danish Psychological publishing

- Systemic Coaching: A Primer, Hanne V. Moltke and Asbjørn Molley, editors. Danish Psychological Publishing, 2009

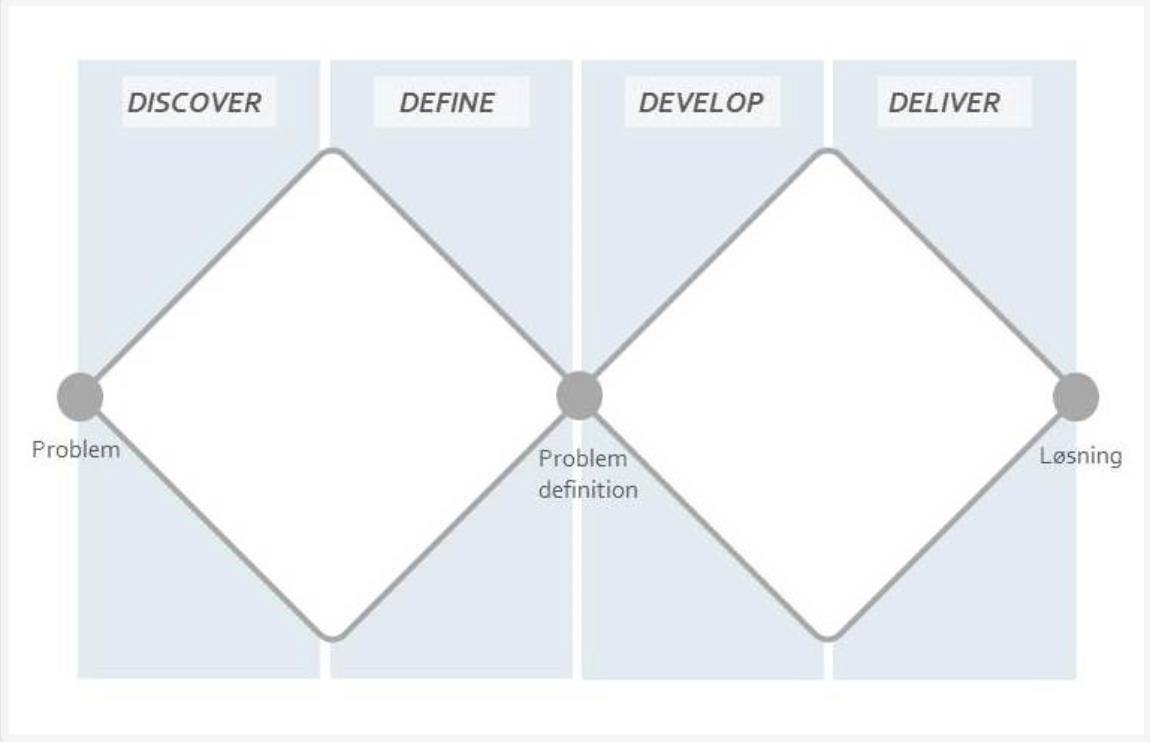

Double Diamond

Double Diamond is a process model that is particularly suitable for structuring a process in relation to external collaboration, qualification of solutions and user involvement, e.g. for an external client or in relation to project development.

In relation to educational elements, the model is good for structuring a course in relation to external collaboration and user involvement in the development of solutions.

The model presents four main phases within two diamonds: Problem understanding – Problematization – Development – Delivery.

Each phase is characterized by either divergent or convergent thinking, where:

– Discover practice is about investigating, exploring and understanding the problem complex.

– Define practice is about delimiting and defining a clear problem that needs to be solved.

– Develop practice focuses on the solution process itself.

– Deliver practice is about tests and evaluation to make the concepts ready for production and implementation.

The model is taken from the University of Copenhagen’s innovation site. Read more about the model here

Sources:

The Double Diamond process model was developed by the British Design Council in 2005 and is a graphic description of the design process. The model is based on case studies of the design departments of 11 global companies, where four generic phases were identified and described in this process model.

A study of the design process – The Double Diamond. Design Council (2005), chapter “The Design process”

E

Effectuation

Effectuation refers to a non-linear approach to working in a non-causal process. As such, the approach is applicable to the artistic practice and business, which often cannot be placed into a predetermined causal context. The basic premise of effectuation is the idea that the future can be influenced through actions. In other words, one creates one’s own possibilities. The method is developed by Sara Sarasvathy. Sarasvathy’s theory of effectuation describes an approach to decision-making and action in processes in which one identifies the best next step toward reaching one’s goal based on the resources available. Along with this, one can also adjust their direction in relation to the outcome of their actions.

Effectuation goes against causal logic in which one defines a firm goal and makes a detailed plan of the path they will take to reach it. This causal approach is often inappropriate for use in processes characterized by unpredictability and uncertainty, such as the process of innovation in the artistic practice and business. The basis of the method is what Sarasvathy calls the Pilot in the Plane Principle. Sara Sarasvathy is a professor at Virginia University. She developed the basic principles of the theory of effectuation in 2001 and still works with it intensively today.

In 2007, Sarasvathy was named one of the 18 best professors of entrepreneurship by the magazine Fortune Small Business. She received an honorary doctorate from Babson College in 2013 for the impact of her work on entrepreneurship education. Read more about effectuation and get the CAKI Miniguide: Effectuation here.

Learn more about effectuation in CAKIs Miniguide: Effectuation

Evaluation

Think ahead!

Evaluation can happen continuously as well as when the project is completed. Often the evaluation is downgraded because it may seem unnecessary to spend time looking back when the project is underway or already well over. But the evaluation is an important tool for you and others to learn from the experiences that have been gained in the process. By reflecting on the process and learning from any mistakes, you also get a chance to make up for bad habits and set new guidelines for future projects. You should plan for evaluation during the various project phases so that it is an integral part of the project plan from the start.

Involving all of the team

Everyone involved in the project should participate in the evaluation. Depending on their role, they may be involved to varying degrees. The evaluation can take place both individually and in plenary. Individually, eg in writing, because it gives the individual the opportunity for anonymity. Plenum because the dialogue between different parties can create new thoughts and ideas. And one should not underestimate the importance of everyone meeting at the end and having the opportunity to say what they did not get to say in the process, pat each other on the shoulder and round up the work. It is rarely to be considered a failure if you did not achieve exactly the goals you had defined in the beginning. It may be that you have learned something new from the turn the project took, and you have led the project in a better direction, changing goals and success criteria as the project unfolded. Therefore, evaluation should not be a cash settlement of goals and results. Instead, focus on what you have learned from the project and what knowledge you can pass on to others. It is the knowledge that is valuable.

Questions for the evaluation

The evaluation begins with the goal you defined for the project, to begin with. Therefore, start by reviewing vision, goals and sub-goals, and then ask each other:

Did we deliver what we were supposed to?

- Did we deliver on time?

- Did we deliver quality?

- Did we meet the budget?

- Did we work well together?

Then you can look ahead and ask:

- What could we do better?

- What did we learn that we can use next time?

- What learning can we pass on to others?

Feel free to pick up on the questions and discussion in a text document that can be shared with those involved in the project. This could be useful if you or other members of the team need to do a similar project some other time.

Evaluate on an ongoing basis

Even if it is a project without a specific end date, eg a company or an association, it is still relevant to evaluate on an ongoing basis. Especially because you have the opportunity to influence the work while it is going on. The evaluation can take place as an ongoing activity, which can advantageously be carried out after you have completed milestones in the project. For example, after a presentation, settlement of an event, in dialogue with the customer when they have tried a product etc.

Reporting

If the project is a study project or supported by a foundation, you may have to make a report at the end of the project. Perhaps the foundation or other project partners require that results and experiences of the project are made visible for a larger public. In this case, you have to meet the requirements that are being set – otherwise, you risk losing the money that has been granted to the project. It is often crucial that by the end of the project you can share the results you have achieved.

You can do this in many ways. You can, for example, disseminate the project using:

- A publication

- A film

- A blog

- A website

- A reflection report

- A presentation

- A logbook

- An infographic

- An article for a trade magazine

For more information:

https://caki.dk/project/ideudvikling-projektledelse/?lang=en

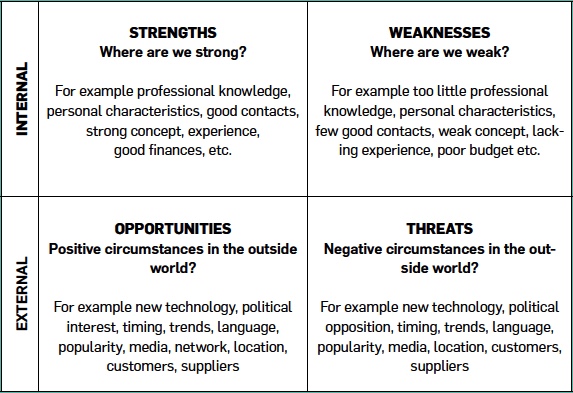

External analysis

-

target your communication

-

see which factors affect your practice and business in which ways.

-

work strategically

- first you put names or places, in relation to who you want to reach – e.g. fans, the audience, your teacher, your fellow students, journalists, bookers, Roskilde Festival, KODA, Kunstfonden…

- Then you make a list of media through which you can reach them – e.g. TikTok, applications, press releases, flyers…

Externalization